From the beginning of the Ukrainian revolution until the Russian annexation of Crimea, US officials and politicians have pointed to Russia’s aggression and disregard for international law.

While it is constructive to point toward injustice when it occurs, it should be done while engaging the age old truism of universality: one should hold others to the same standards one holds themselves. It is through this prism that we should evaluate our own leaders’ statements and actions.

Let us begin with John Kerry, who while explaining the US stance on Russia’s “incredible act of aggression” said “You just don’t in the 21st century behave in 19th century fashion by invading another country on a completely trumped up pre-text.”

Though referring to Russia’s invasion of Crimea, he perfectly described the 2003 US invasion and occupation of Iraq, which violated the UN charter and Geneva Conventions. According to Benjamin Ferenccz, a prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials, these acts constitute “a supreme international crime.” The “trumped up” pretexts used were the weapons of mass destruction and the Saddam – Al Qaida links that, according to our own intelligence experts, never existed.

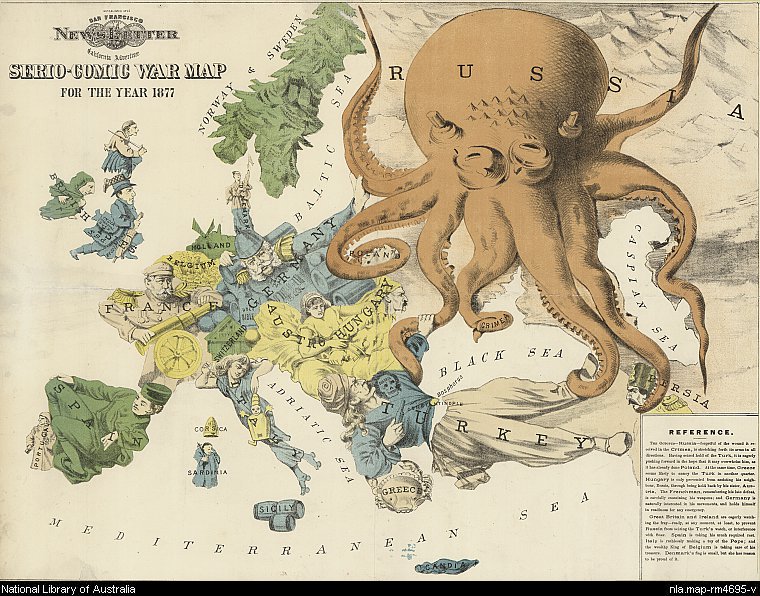

It should be noted that Kerry referenced “the 19th century” rather than the 20th. Violating international law, acts of aggression and intervening in sovereign nation’s affairs was (and still is) the basis for US foreign policy during that century. A brief look at its policies toward Latin America and the Caribbean throughout the century provide sufficient examples.

Attempting to build the case against Russia, Obama has remarked “we are well beyond the days when borders can be redrawn over the heads of democratic leaders.” We should remind ourselves that the US has provided military, economic, and diplomatic support for Israel which for nearly 50 years has ‘redrawn’ the map of Israel and Palestine through an illegal occupation and annexation. The voting record in the United Nations shows that the US is consistently the only country (besides Israel) to veto the countless General Assembly and Security Council resolutions condemning Israel’s actions.

Keep in mind that Crimea houses Russia’s largest naval fleet. What actions would we support if a US naval installation was threatened? The year 2011 is instructive. When the Arab Spring swept into the small island nation of Bahrain (home to the US 5th naval fleet) our close ally Saudi Arabia violated Bahrain’s sovereignty as it sent in tanks repressing peaceful protesters’ democratic demands. Repercussions for Saudi Arabia included White House spokesman Jay Carney describing the 1,000 troop incursion as “not an invasion of a country” and a $30 billion dollar weapons deal.

If sanctions and international isolation are the proper response to Russia’s actions, then what is to be made of our actions and those of our allies? History is said to be the final judge. Yet, when that judge decides in the wrong fashion, history itself must be erased. Thus, John Kerry overlooks a century of US foreign policy and President Obama recasts aggression against Iraq as an instance when “America sought to work in the international system.”

FOREIGN POLICY: WEAK OR STRONG?

Despite the facts above, the ‘debate’ in the US government has remained narrow. Congressional hawks are politicizing Crimea, attributing it to a “weak” foreign policy pursued by the current Administration. They contend it is because President Obama did not take a hard stance, allowing Russia to realize it could ‘push the US around’. In the words of Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC), “we have a weak and indecisive president that invites aggression.” Others cite drawing a red-line on Syria, and then backing down, as another example of weakness. The argument crumbles under closer scrutiny.

Take the last four presidents who most observers agree pursued a “strong” foreign policy stance: Eisenhower, Johnson, Reagan, and Bush II. The first three oversaw foreign policies centered around “being tough on Russia,” nevertheless Russia invaded Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, and escalated its war in Afghanistan in the ’80s. Finally, under Bush II, Russia engaged in a war with Georgia in 2008. There is little historical correlation between the “strength” of US foreign policy and the likelihood of Russia invading other countries.

The arguments put forth by the foreign policy hawks ignore history, but also a more important voice: the people. In the case of Syria, public opinion polls indicate that nearly 72 percent of the US public was against any military action. Similarly, a recent Pew Research Center poll taken on the Crimea issue found that 52 percent of Americans thought the US should “not get too involved in the situation” and only 35 percent thought it should “take a firm stand against Russian actions.”

So the question arises: Is abiding by the democratic process (the value that has made the United States the proclaimed ‘beacon of light’ for the world) a strength or a weakness? Hopefully it doesn’t warrant too much thought.