Inspired by the upcoming Academy Awards, the New Context staff is reviewing international films.

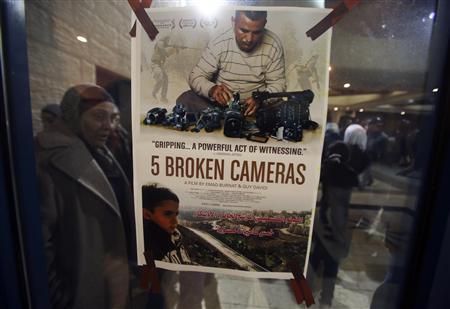

“5 Broken Cameras” is nominated for the Oscar in the Documentary Feature category.

Emad Burnat, a farmer in the West Bank, never planned to make a documentary film. But when his son Gibreel was born in 2005, he bought his first camera to record his new family life. That same year, the Israeli government began construction on settlements and the West Bank Barrier, a separation wall going throug Bil’in, the village of about 1,800 where Emad lives with his wife and three children.

As the bulldozers destroyed their land and uprooted their olive trees, the people of Bil’in united in a show of nonviolent resistance. Despite the mostly peaceful nature of their weekly marches and demonstrations at construction sites and settlements, Israeli soldiers responded with arrests, tear gas and gunfire. Many protesters were injured and several were killed.

5 Broken Cameras is told along a timeline of Gibreel’s first years—as the boy turns four, so does the resistance—and Emad’s cameras are used as benchmarks of the resistance in Bil’in. His first camera is shot by Israeli soldiers. His second camera is knocked to the ground as he filmed construction at a settlement. By Gibreel’s third birthday, Emad is on his third camera, soon destroyed by gunfire.

As the title suggests, Emad’s relationship with his cameras is a major theme. His position behind the camera during every protest gives him a false sense of protection. Though filming is therapeutic for him, the moral vagaries of documentation crop up. In one particular scene, as Israeli police are arresting his brother, he watches through the camera while his mother and father jump on the army vehicle while shouting at the police. The village children watch from a nearby rooftop, and at that moment Emad is conflicted, unsure whether to continue filming or fight for his brother. He kept filming. “I have to believe that capturing these images will have some meaning,” he said.

By involving Gibreel rather than shielding him, Emad reveals his uncompromising attitude toward capturing the popular struggle: “The only protection I can offer him is allowing him to see everything with his own eyes, so he can confront how vulnerable life is.”

I was skeptical about Gibreel’s central role in the film, questioning his judgment and wondering if his son’s presence was a form of emotional exploitation. But Gibreel’s character is legitimate because he is an active part of the resistance. Some of Gibreel’s first words include “wall” and “army,” and in one memorable scene, an Israeli soldier lets the family through the gates of the separation wall after Gibreel offers him an olive branch. Emad’s children, along with other neighborhood kids, participate in the resistance activities. And in the family’s yard, gunfire is standard background noise.

Israeli director Guy Davidi worked with Emad to stitch the archival footage from the five cameras together—and Emad was criticized for the partnership. “Palestinians and other Arabs came up to me and asked how I could work with Israelis,” he told the New York Times. But Davidi had been involved from the beginning, arriving in 2005 to shoot a documentary on Palestinians who take settlement construction jobs. As Emad noted of the movement, which drew a diverse crew of sympathizers, “From the start, the struggle for Bil’in involved Israeli activists.”

Though it felt disjointed at times, with too much filler of birds flying across a West Bank sunset, it’s clear why 5 Broken Cameras is nominated for an Oscar. The narration is thoughtful and honest; the story is important and at times, heartbreaking. His passion, bordering on obsession, for capturing everything on camera—not just the protests, but celebrations, lazy days, and everything in between— forces the viewer to remember that the fleeting images on the screen portray just a sliver of life during the battle in Bil’in.