Recent events in Ukraine have driven a return to a debate that has long simmered below the surface — between the U.S. and Western Europe on one side and Russia on the other. There have been many cold war analogies drawn about the Ukraine conflict in recent weeks, most of them irrelevant or simply wrong. Still, the context of the current debate has primarily been framed as one of ideology between what were the Cold War powers. This context has no correlation to the world we live in today, yet the vast majority of public discourse about Ukraine’s future is taking place through the lens of this outdated frame of thought.

Thought leaders in the United States and the Russian foreign policy community acknowledge that the world has changed dramatically in the past quarter century. The global economy has become irrevocably intertwined. Yet when it comes to areas in which the U.S. and Russia have competing interests, politicians and pundits inevitably return to outdated Cold War rhetoric. The aging foreign policy elite, who guide Russian, European and American international policy, don’t have the flexibility of thought to move beyond these calcified notions ingrained during a Cold War coming of age.

In practice, the world has changed so drastically in the past 25 years that the Cold War notion of a dichotomous and antagonistic East versus West world makeup falls flat on its face when confronted with economic, political and social reality. Hence, in the current standoff in Crimea, when Russian president Putin moved aggressively to pursue his interests in the region, the U.S. and EU, responded by threatening sanctions, and the Russian stock market promptly dropped 10 percent the following day. While this may have led Putin to soften his stance in a 90 minute press conference the following day, the EU also was given reason for pause when the European stock market faced pressure and natural gas prices spiked. Any economic action against Russia would also have major financial implications for Europe, which gets most of its natural gas from Russia, and in particular Eastern European nations, which have significant trade ties to the Russian federation.

If we acknowledge that the Cold War reality doesn’t exist today except in the minds of American and Russian elites unable to move beyond ingrained patterns of thought (but who currently monopolize debate in the primary channels of mass communication), we can begin to evaluate the hypocrisy in the ideology in each of these two imagined antagonistic sides and may begin to find more plausible real world solutions based on the present day situation in Ukraine.

For the U.S., it is hypocritical to ignore that the outsize economic influence of the United States translates to political power which the U.S. uses to its considerable advantage. It is hypocritical to argue on one hand that mass protests in Ukraine which led to the flight and (not entirely constitutional) impeachment of Ukrainian president Victor Yanukovych are legitimate democratic action, but on the other that movement for self-determination by the population of the semi-autonomous Crimea region (which overwhelmingly identifies as Russian) is illegitimate. This is especially hypocritical in light of a long standing history of U.S. policies in support of non-democratic governments. Furthermore, both the U.S and Europe face underlying tension in many dealings with other parts of the world (particularly so with Russia) as a result of an inherent implication that Western know-how is the best solution to all political problems.

For the Russian Federation, it is hypocritical to hold state sovereignty as one of the core principles of its foreign policy concept, and to argue vehemently against any type of intervention, including those with humanitarian aims on the one hand, but to support a Crimean separation from the Ukrainian state, and meddle in Ukrainian sovereignty on the other. It is hypocritical to allow well-armed Russian troops to move off Naval bases in Crimea and label them “local self-defence units” but label unarmed peaceful protesters in Kyiv terrorists and Nazis.

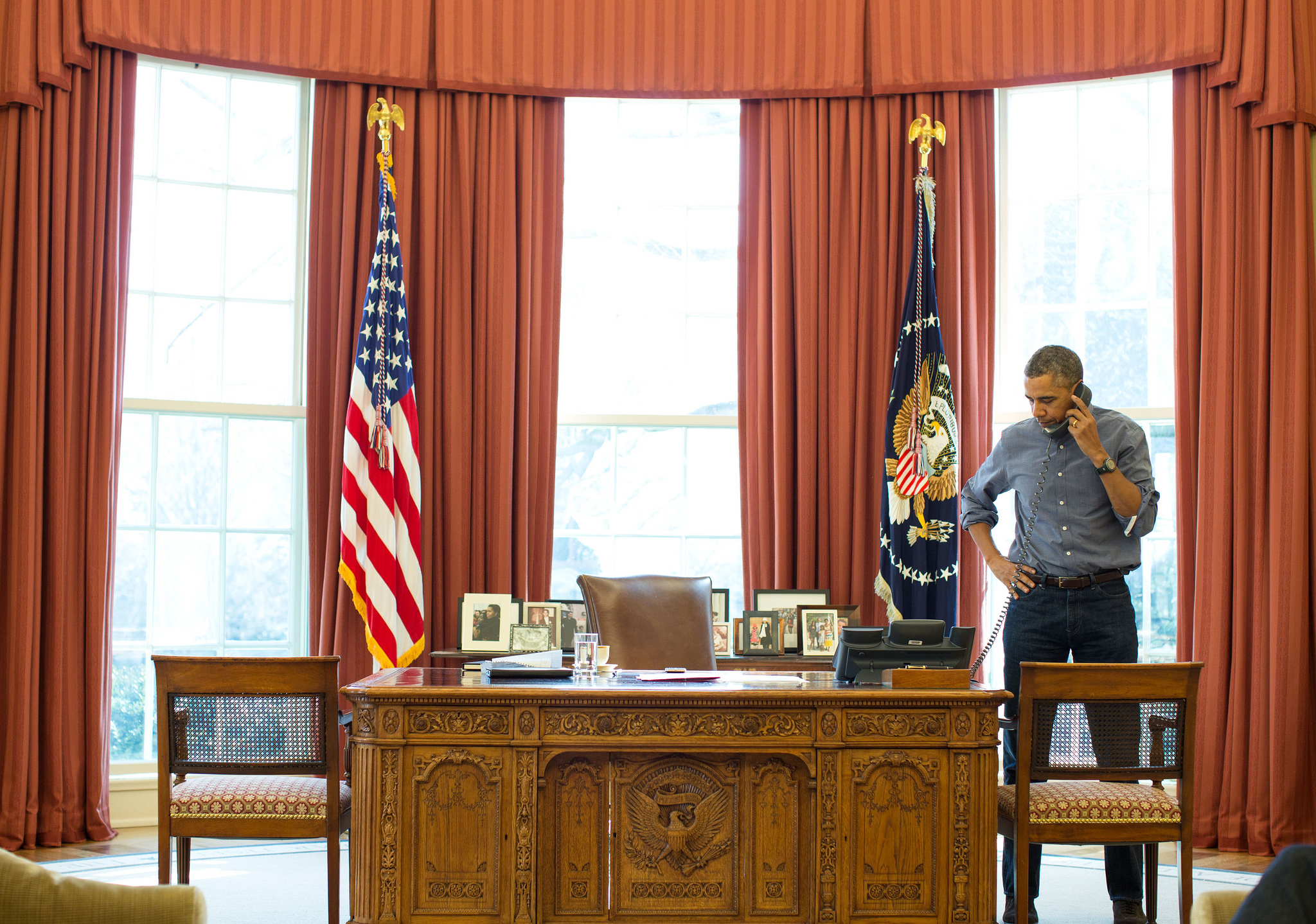

This hypocrisy should be obvious to anyone who lives and functions in the real world. To those outside the U.S. and Russia it must seem very childish. In truth, most of the time, those in the Kremlin and the White House spend most of their time working in the post-Cold War reality. But when it comes to international conflicts in which both the U.S. and Russia have vested antagonistic interests the blinders come on. The outdated paradigm inevitably creeps back into the minds of Russian and American leaders who unsurprisingly, and understandably are working from a standpoint of decades of mistrust.

Political change is messy, but it is a trait of the complex period in which we live. Globalization of world economies and democratization of global media have raised the collective intelligence of the world to a level unparalleled in history. This requires an equally flexible international response that paves a path toward a mutually beneficial future attuned to the political and economic realities in which we live. A future that is being built regardless of American and Russian policy. The global economy of the 21st century doesn’t operate on the zero sum basis of the Cold War, and the U.S. and Russia are no longer the only players on the world stage. We either win together or lose together, there is no in between. The faster that those in positions of influence in Russia and the United States can get out of their own way, and work together as integral parts the interconnected and complex international community in which we actually live, the faster we will move toward solutions to real world problems.

Well put. The mainstream media is both manipulated by the political punditry and inherently complicit in reinforcing the simplistic Cold War narrative, which is easily fed and lapped up.

One quibble: “For the U.S., it is hypocritical to ignore that the outsize economic influence of the United States translates to political power which the U.S. uses to its considerable advantage.”

Whether or not the U.S. govt is open about it’s soft power, which the Crimea affair betrays as weak (if one wants to use this context), this is one of the lesser hypocrisies. The various hypocrisies from various interests on all sides are simply the realism of a complex issue in a self-help, self-focused world. Thus hypocrisy in almost any U.S. and Russian foreign policy, which is based on self-interested motives (and often of the self-interested critics of those policies), is self-evident, especially when these policies are shortsighted and reactionary, which is almost always the case (see Arab Uprisings).

I reject the premise that we live in a “self-help, self-focused” world. That was likely an accurate depiction of geopolitics up until the 1990s, but since then – and especially in the past decade as a result of the information economy – the wold has moved away from the realist paradigm at an exponential rate. The impacts of this change are still being understood, but suffice to say it is not zero sum.

In this context in which the U.S. and the Russian Federation are not the only players – though they are large and powerful players, there are far greater gains to be had for all states, and all individuals, by continuing on the path of 21st century cooperation. In fact I would argue that the only way for gains to be had is now through integration on an international, global level.

In the realist paradigm the only possible alternative would be a retrenchment to state power bases (China, USA, Russian Fed…) and international disengagement which would in effect cost the world so much financially that it would be politically impossible to achieve.

With this in mind, the U.S., by framing its actions or reactions in the irrelevant realist paradigm while attempting to portray itself as a global leader in the new international paradigm, is guilty of perhaps the most serious hypocrisy. At least President Putin wears his realist ideology on his sleeve. By appropriately framing actions and reactions based on this 21st century paradigm the U.S. would be in a position to lead the world in a more congruent way.

Certain aspects of the realist paradigm are out of fashion and the international system of states is more complex than a simplistic realist view, I will certainly grant that. But history and geography prove patterns. Besides, as you point out, the US is responding in realist zero-sum fashion couched in the usual liberal rhetoric. Whether realism is passé, or whether it works or not, doesn’t change that geopolitical balance-of-power theory (keeping a potential regional hegemon in check) motivates US foreign policy actors. In any case, we know there are different schools of realism. Kaplan’s geographic quasi-isolationism would see that history and geography show that Russia holds all the cards and the US is wasting its time on irrelevant moaning. Russia will never truly let Ukraine—Russia’s birthplace, breadbasket and resource hub—out of its orbit; Russia has been for six centuries an insecure landpower that expands and contracts consistently; it is a classic European problem that European geopolitics and great powers such as Germany will handle. And the US should be grateful for its unique water security of two oceans, its regional hegemony security, and spend time trying help the potential failed state of Northern Mexico.

In any case, I agree with everything you say except for that realism is dying. If realism is not in fashion (and the rhetoric never is), its proponents will nevertheless re-assert themselves with strong logic.