ALIX SCHRODER

Being a first semester graduate student and newcomer to New York City, last semester was a blur of activity for me—school, school and more school, events, meetings and the feeling of being constantly lost. Within all the chaos, however, three things in particular stand out:

1. Seeing Joseph Stiglitz speak: I have to admit, I am a bit enamored with Joseph Stiglitz. In my last year of undergrad, I read his book, Globalization and Its Discontents, for an International Political Economy course I was taking. Until that point, I had considered economics to be a yawn-inducing subject only business majors would voluntarily subject themselves to. Stiglitz’s book, however, completely changed my outlook on the importance of studying economics in international affairs. Seeing him speak in person last semester about his most recent book, The Price of Inequality, was not only a dream come true for me, but also a very illuminating and thought-provoking experience. He spoke to the cultural and political consequences of concentrated wealth in the U.S., offering solutions and relevant international context. Stiglitz is a rock star.

2. Nerding out about school work, outside of school: I can’t count the number of times during the fall I found myself out with fellow GPIA-ers discussing authors, articles and theories from our classes. Over a cup of coffee, we debated Polanyi’s “fictitious commodities” and Marx’s “commodity fetishism.” At dinner, we traded views on humanitarian intervention and Hannah Arendt. Out for drinks, we discussed final paper themes, economics assignments and school events. For the first time, I found myself surrounded by people who were passionately interested in the same things I was: the most recent election in Egypt, women’s rights in India, the Arab spring, Brazil’s rising economy. The bonus? I discussed all these while out in the city, with a glass of wine or bottle of beer in hand.

3. Making the connection between real life and theory: Reading Gavin Fridell’s article, “Fair Trade Coffee and Commodity Fetishism: The Limits of Market-Driven Social Justice,” was also a highlight of last semester. His article explores the notion that the fair-trade network provides an initial basis for a challenge to the commodification of goods under global capitalism. Before moving to New York for school, I worked for a nonprofit organization dealing exclusively with fair trade. I loved Fridell’s article because it helped make a connection between academic theory and the “real world” work I had done. Often I’ve felt that the theories we learn in class are rarely applicable to the professional world, so this reading was both refreshing and insightful.

BRITTANY DUCK

As Spring semester is here with syllabi chock full of new reading material, I was inspired to take a look back at some of the most memorable books and articles from Fall 2012.

Decolonizing International Relations – Branwen Gruffydd Jones

An assortment of scholars use postcolonial theory to analyze contemporary international relations topics, such as human rights, global governance and international law. This work stands out as much for its authorship as it does for the perspicaciousness of its criticism. Contributors come from around the world, including from universities throughout the global South. Noteworthy chapters include Antony Anghie’s “Decolonizing the Concept of ‘Good Governance'” and Siba N’Zatioula Grovogui’s “Mind, Body, and Gut! Elements of a Postcolonial Human Rights Discourse.”

The Decline of the Nation-State and the End of the Rights of Man – Hannah Arendt

In this chapter from her seminal book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt, levels a damning critique of human rights idealism. Arendt highlights the contradiction that exists between citizenship rights, which were once theorized as the supreme guarantor for a given political community, and human rights, which were elevated above citizenship rights despite lacking mechanisms for enforceability. In an age dominated by human rights discourse, which is routinely taken up by governments, civil society organizations and individuals, Arendt’s work remains a salient critique.

Global Governance and Revolution in the 21st Century: Strikes, Austerity and Political Crisis – Steven Colatrella

In light of numerous high-profile strikes in Chicago, New York City and Wisconsin, Steven Colatrella’s article on contemporary global strikes is an especially pertinent read. Colatrella argues that the 21st century has seen the greatest wave of worker strikes in human history. Colatrella also offers a wider challenge to the concept of global governance, alleging that the EU, IMF and WTO are tools to insure the maintenance of a class-based hierarchy. Given the re-emergence of the strike as a political tool, Colatrella’s claims about the future of political authority warrant serious consideration.

MICHAEL QUIÑONES

Economics as oppression

The most important thing I learned during my rookie semester is that all things have been commodified. As the financial collapse and the tax-payer bailout have exemplified and the Occupy movement has underscored, market economics reinforces a neoliberal “haute finance” media complex that must monetize and sell everything. The main reasons to study economics are to understand the pseudo-philosophy’s detriment to modern society and to question every mathematical theory used to develop policy. Economic growth is not an inherent good; it is a metric of concentrated wealth. Mismeasuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn’t Add Up by Joseph E. Stiglitz, Amartya Sen and Jean-Paul Fitoussi takes on the most obvious example of what’s wrong. When supplementing it with books such as Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation, it is hard to dispute that economics has become merely a political weapon for the elite, a convenient shorthand for the mainstream media and a ruse perpetrated on the 99 percent. As long as we measure our lives in the language of capitalism, we will never get beyond equating goodness with shiny new things.

Mahmood Mamdani, jury’s out

A surprisingly fun exercise of the semester involved having Mahmood Mamdani built up for me and then torn down again—plus his visit, which we were all excited for, was canceled due to the Fall 2012 superstorm. Media criticism and the power of language fascinate me (I struggle to avoid Chomsky worshipping), so Mamdani’s “The Politics of Naming: Genocide, Civil War, Insurgency” was a revelation for this IA neophyte. It offered a simple lesson: Nothing is simple, no matter how many impressionable collegiate quasi-activists think so. It offered the paradox of military intervention: It’s hard to tell whether doing nothing is better, either in terms of Western politics or the quality of life of those who often plead for assistance. When we were assigned Richard Just’s critique of both Mamdani’s Darfur book and Gareth Evans’ Responsibility to Protect—a modern justification for imperialism—it was pleasure reading. In somewhat of a shock to me, Just took Mamdani to task for the biggest sin in journalism and science, allowing preconceived notions to dictate the story. Just tars the book as a made-up controversy—comparing the Iraq War with West Sudanese devastation—yet Mamdani’s message is far from lost.

AMBER KIWAN

Looking back on the stacks of books and articles I read last semester, it’s clear that some were denser than others. For example, Hobbes’ Leviathan, which is filled with complex, antiquated language, was not the easiest to digest. One of the most compelling pieces was King Leopold’s Ghost, by Adam Hochschild. It is a factual account of Belgian colonialism in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, told in shocking detail, with a unique focus on smaller characters who didn’t hold all the power, but played key roles in what Hochschild calls the “story of greed, terror, and heroism in colonial Africa.” His writing is consuming, whether or not you are an international affairs junkie. The piece puts the reader in the moment, telling the story from the point of view of the characters, a perspective rarely found in news coverage of conflict or political analysis of historical events.

A highlight of Fall 2012 was taking advantage of the surprising amount of events at both The New School and around the city. I have a journalism background, and I gravitate toward media-related discussions. Justin Elliot from ProPublica, Katrina Vanden Heuvel and Richard Kim from The Nation, and Chris Hayes from MSNBC are just a few journalists who gave talks at The New School. Listening to leading thinkers and writers discuss, ask, answer and debate has been supplemental learning for me. The countries, policy issues, conflicts, and theories we’ve been learning about in class are infinitely complicated and multifaceted—for every aspect we learn about, there are the related opposing thoughts, instigating events, people who influenced the decisions, connective pieces and delayed, residual effects. All of it is applicable and relevant to current events and participating has helped to bridge the gaps and connect theory to practice.

MARCELA GARA

With one semester left and graduation looming, reflection on grad school already seems to be kicking in. From Fall 2012, my biggest takeaway was and is an increased critical perspective on most if not all media—especially when it comes to media campaigns.

Take for instance my Media and Culture course, where we watched the Water Is Life campaign that ingeniously turned the hashtag “#firstworldproblems” on its head. The campaign filmed various Haitians reciting average problems from the developed world. It can be uncomfortable to watch—which may be the point—because in comparison to living in a country struggling to attain clean drinking water, a dead cellphone is irrelevant. Yet, my peers and myself questioned its effectiveness and ultimate goal, and considered the serious “first world” problems countries like the US do face.Homelessness, gun control and extreme poverty, just to name a few, are serious “first world” concerns that go easily unaddressed by this campaign. Moreover, does this sort of media campaign actually provoke action or does it simply want you to donate money? And, if the end goal is purely monetary, does a campaign like this reach a majority of Americans or actually alienate most? It is these sorts of concerns and questions that seem to pop up more than ever, making me realize how I’ve changed—maybe I ask too many questions now—but mostly, that nothing can be taken at face value. Media campaigns should be dissected, analyzed, and even reconstructed for the better. But ultimately, like the Water Is Life campaign, media should ignite dialogue.

Watch the Water Is Life campaign video and tell us what you think:

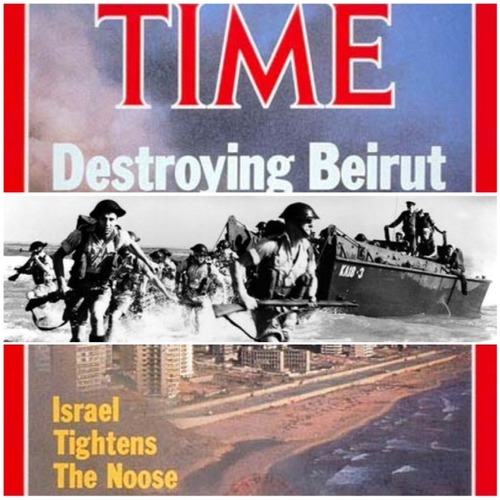

Last fall also made me more interested in the use of visuals to incite conversation. Living in a culture where our exposure to photos, videos, media, news, Twitter, etc has grown exponentially, I was excited to come up with a final project that could do this through images. For the same media class, my group and I created a Tumblr called “Juxtaposing American History.” We thought about dates in history and how some had become synonymous with America, such as September 11th or July 4th. These dates also hold similar meanings for other countries, which are often overlooked or simply never taught in school. The point is not to diminish the events that took place in the U.S., but to shed light on the fact that these dates and moments are universal and, at times, even ironic.

Here are a few of the images. Read about the significance of these dates here.

[portfolio_slideshow id=488]