Viktoriia Gudyma, 30, is a Ukrainian runner, cyclist, and mother. We met in 2020 in Moldova at the Milestii Mici wine run, an annual 10-kilometer race through the largest wine cellar in the world. Participants wear headlamps and run through the narrow, winding underground labyrinth lined with barrels of Moldova’s world-famous wine. Viktoriia and I happened to stay in the same room at City Center Hostel and bonded over being outsiders in Moldova and our love of running. We took the bus to the race together, exchanged social media information, and then went our separate ways. Over the past two years, I have occasionally seen her finish line photos on Facebook at different races around Europe. Recently, Viktoriia has posted on social media speaking out against the violence in Ukraine, so I reached out to her to check in; we video chatted on April 12.

Viktoriia was born in Ukraine in 1991, the year the Soviet Union collapsed and Ukraine became an independent state. She grew up in the center of Ukraine in the city of Vinnytsia. During her childhood, Viktoriia’s family struggled financially due to the recession and inflation throughout the country, but she did not find that out until she was older. She just remembers the happy times spent studying, playing with friends, and working in her grandmother’s garden.

More recently, Viktoriia lived a peaceful life in Kyiv with her son Leo, 10. Viktoriia and Leo shared an apartment in the city center near the University and Golden Gate metro stations. Viktoriia worked remotely for an Israeli game development company and trained in her free time. Leo attended 4th grade and took music lessons after school.

“I had a normal life with my son. I went to the theater. I went to cafes,” Viktoriia reminisced. “Have you ever been to Kyiv?” she asked. When I shook my head, she said, “I would like to show you when it is safe.”

Viktoriia read the news predicting the outbreak of war in Ukraine, but she did not believe it would really happen.

“I couldn’t imagine the long-standing city of Kyiv – in Europe geographically and the nearest neighbor of the European Union – could be attacked,” she said.

Viktoriia’s apartment was about a kilometer from the national opera house, so she would go to the entire season of performances. On the night of Feb. 23, Viktoriia went to the theater with her friend and had what she described as a normal evening.

Early in the morning of Feb. 24, Viktoriia woke up to a phone call from her friend living in Obolon, a residential district in the northern part of Kyiv, calling to inform her that the city was no longer safe.

“He said, ‘War has started, take your son, and go from the city,’” Viktoriia remembered.

Viktoriia went to the kitchen, opened her laptop, and messaged her company who told her to do whatever she needed to do for her safety. She shut her laptop and went outside. As she looked down Victory Avenue, which was in complete gridlock, Viktoriia realized she would not be able to leave any time soon, so she walked to the supermarket to buy some food. The lines were long, and an atmosphere of anxiety hung over the city. Her next task was to acquire gas for her car.

Viktoriia told me that life in Kyiv was not perfect before the war; she was irritated by traffic jams, air pollution, and other problems in the capital.

“When the war started and the streets became empty in the first hours of the war, that was terrible. I wanted just to go to the past and have all these problems in the city – traffic jams, people rushing to work, angry people in the streets – but not this war,” she said.

When the air raid warning sirens sounded, Viktoriia and Leo went to the Golden Gate metro station. She was surprised by how many people were crowded into the station with children, dogs, cats, and even birds. She did not bring warm clothes with her because she did not realize how long they would need to stay there. Viktoriia and her son returned to their apartment to gather blankets to keep them warm and books to keep them occupied.

Viktoriia and Leo spent part of the night in the University metro station. They sat on the floor of the station which is made of cold Carpathian marble. Then they went to sleep in their apartment. Viktoriia sent Leo to shelter in the bathroom for safety.

“The first time, he was smiling because we put pillows and blankets in the bathroom like a nice game, but it was not a game,” Viktoriia said.

Leo said “Mom, we are going to sleep. When we wake up in the morning, everything will be like previously, like yesterday.” And Viktoriia responded, “No, tomorrow it will not end.”

In the morning, the sirens signaled that it was time to go back to the metro station, but Viktoriia decided it was time to leave the city. She knew she was taking a risk. As they drove through the city, they saw destroyed buildings and heard sounds of explosions. She picked up her colleague Alexey and his girlfriend Daria. This was the first time they had met in person since they normally work online.

After picking up Alexey and Daria and putting their limited luggage in her car, Viktoriia drove 20 hours west to Lviv, a journey that normally takes less than half that time. As the only one in the group with a driver’s license, Viktoriia drove the entire way by herself. She had to avoid her usual route, because they had heard that fighting was taking place there. The group planned to stop in Viktoriia’s hometown Vinnytsia for dinner and rest but, when they arrived, Viktoriia’s relatives told her to keep going. Her ex-husband bought her 50 liters of gas in a special tank and told her it was time to go.

When the group of four reached Lviv, they picked up Viktoriia’s friend Vlad who drove the next night. They continued to steer clear of the main roads for safety, but the side roads did not have lights and were filled with potholes, so the driving was challenging.

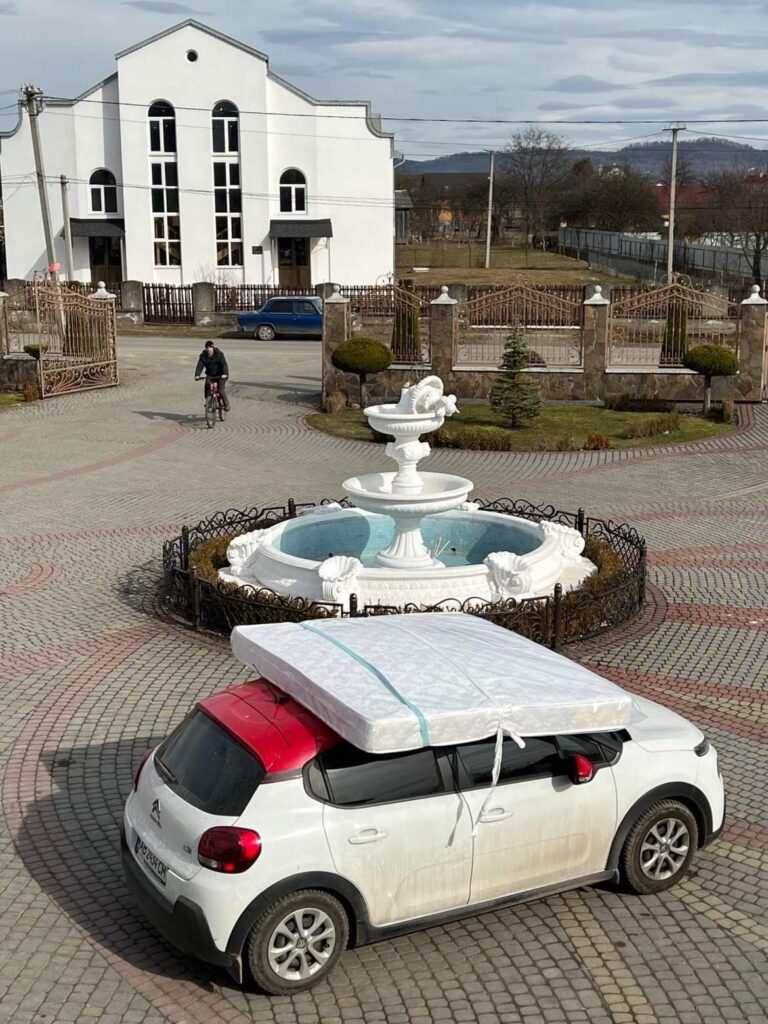

The group of now five people spent a few nights in western Ukraine in the Carpathian region. They slept in an old house in a small village not far from the Romanian border. There were mice in the house and a hole in the roof; they cleaned it and made some repairs. They drove to the nearest town and bought a mattress which they transported on the roof of the car. Viktoriia laughed when she told me about that. The group did not cross the border at this point because they held out hope that the war would be over soon. Viktoriia hoped that other countries would intervene, and she could go home.

While they were staying in western Ukraine, the two men in the group received documents ordering them to serve in the local defense. Now the group was only three. Viktoriia decided they should go to Poland through Hungary, because the line of cars from Lviv to Poland was several days long and she was worried about spending the night in that line. The group crossed the Hungarian border and drove through Hungary and Slovakia and into Poland. They spent a night at Viktoriia’s friend’s apartment in Krakow and, the next day, went to Warsaw where her company has an office.

Viktoriia’s company put her up in an apartment in the city center for a month and she now lives in a hotel on the outskirts of Warsaw. As she told me about it, she turned the camera around and showed me her spacious and sunny hotel room. Daria also found a place to stay in Poland, a free house offered by a Polish family in the city of Poznan. Alexey is currently in a hospital in Ukraine with inflammation of the lungs, and Vlad is still serving in the defense.

The first few days in Warsaw, Viktoriia just wanted to see normal life. Even though she could work remotely, she went into the office in the city center. The company provides free breakfast and lunch at the office. Those first days, Viktoriia was extremely hungry; she told me that she ate a lot during that time, gesturing shoveling food in her mouth.

Viktoriia and her son have established a regular routine in Warsaw. Leo attends his Ukrainian school, which is now online, from the hotel room. Leo’s teacher is still in Kyiv, and sometimes their class is interrupted because the teacher must go to the bomb shelter. Viktoriia works from home while Leo does his lessons, and then goes into the office for meals. She runs in the morning or the evening.

Before the war broke out, Viktoriia had registered for the Rome Marathon to take place on March 27. As that day approached, the race organizer reached out to Viktoriia to find out if she was safe and whether she would still be competing. Viktoriia responded with a long letter written in Italian.

“I said I left the city without my clothes for competition. I said I do not know how to live in the future, but I would like to run,” Viktoriia said.

The race organizer was impressed by Viktoriia’s Italian and helped her make arrangements for the race. Athletica Vaticana, an athletic organization associated with the Vatican City, sponsored her trip. Viktoriia told me they became her Italian family.

The day before the marathon, Viktoriia stood in front of news cameras and announced that she would run the race in three hours and 30 minutes. She ran the entire distance with a Ukrainian flag wrapped around her. During the race, Viktoriia’s watch battery died, and she did not have the time. When she reached the finish line, Viktoriia felt like she had been running for five hours but, when she asked someone for her time, she found out that she had finished in 3:28.

While in Italy, Athletica Vaticana invited Viktoriia to an audience with the Pope.

“I did not plan to meet the Pope. I am not Catholic. I am not a religious person. Sometimes I pray to God to ask him for something or to thank him, but I am not really religious,” Viktoriia told me.

Even though she is not Catholic, Viktoriia said that meeting Pope Francis was a very important encounter in her life. She asked him to pray for the children of Ukraine, and he blessed Leo. Viktoriia described the Pope as having really nice, kind eyes and a nice smile. She said it was like a fairytale. Viktoriia emphasized that her story is an exception to the rule – most Ukrainians have not been as lucky.

“My story seems to be a happy story, because I am alive, and I did what I planned. We left Kyiv, and thank God we are alive, but a lot of families are not,” Viktoriia said.

Viktoriia has not officially applied for refugee protection status in Europe yet, because she is currently in the United States to run the Boston Marathon and was unsure whether she would face travel restrictions as a refugee.

“When I left my home, I became a refugee in my own country but, legally, I am not a refugee because I did not get money. But everybody helped me a lot,” Viktoriia said. “In Europe, I have seen a bunch of nice places, but it does not feel like vacation. I would like a stable life at home.”

I asked Viktoriia about her hopes and plans for the future.

“I want the war to end, and I want to see a rebuilt Ukraine after the war. It is not safe to go to Ukraine now because I don’t feel that I have resources to escape again. That was a big effort,” she said. “I would like to create a family and become a mother again. I hope, I believe, and I pray for our victory.”

Viktoriia is focusing on the Boston Marathon and, when that is over, she will figure out where she and Leo will live until the end of the war. She is considering Italy or Great Britain because she has friends in those places. The most important things for Viktoriia are her independence and Leo’s education.

I asked Viktoriia about the significance of running in her life. With everything going on, I wanted to understand why it was so important for her to continue to run.

“When I run in the forest somewhere or on the street, this is for me a type of therapy or meditation. It is a chance to show that something in my life doesn’t change, that I have something stable,” she said.

Unlike in Rome, Viktoriia’s only goal for the Boston Marathon is to cross the finish line. She will be wearing a blue shirt and yellow shorts.

“I am not really prepared. I am not in good shape now, but I want to run,” Viktoriia said. “This is a chance to show peaceful protest, to run with the Ukrainian flag, and ask people to not have ignorance to this war, and to run for peace.”