This illustrated oral history features Delia Martínez, a Mexico-city based photographer who, interviewed by New school student Mariana Sanson, describes the process of photographing Mexico’s largest ever women’s march against femicide and gender-based violence.

Mariana Sanson: This interview is part of a publication that we are going to do for The New School, in The New Context and I am very happy to be here with Delia. I’m going to give you the floor so you can introduce yourself.

Delia Martinez: Hi Mariana. Thank you very much for this space, I am deeply moved and grateful. I’m Delia Martínez Mendoza, I live in Mexico, specifically in the State of Mexico in Ecatepec. I always like to name the municipality where I live because for those who live in Mexico, it is a very popular municipality for many reasons, it has many meanings, between violence, populism, and the social framework and constant migration.

Mariana: Thank you very much Delia. I think it is part of this story and of what we are going to talk about today. This interview is on the occasion of your incredible work that you did on March 8, 2020. Your photographs are very powerful and we are going to start by focusing on that, on that day. So I would very much like to be able to ask you and you tell me what your experience was on March 8, 2020.

Delia: As a photographer, I had always had the concern of reporting in this context in general in Mexico. I had not had the opportunity but last year the stars aligned and I scheduled it. I also felt it very deeply in my being. I do remember that I prepared myself, there were many possibilities of violent situations, but frankly, my protective gear was not because of those who were going to march, it was towards the opposite party, no? towards those who repress us, towards these people who go undercover but are from the state.

I remember that I was a little late because in addition to wanting to go by myself, I have been involved in a group of women photographers in Mexico for a couple of years, so to have a safety net, we created a group where we were going to be monitoring each other throughout the march.

I remember that I took a bicycle, I thought it is the best way to go because obviously everything was closed and I pedaled and I could not believe what I was seeing, ten blocks before the Monument where we were going to meet, there was a sea of people walking, most of them were women, and from that moment my heart was already beating because no, I did not know what I was going to find, but I knew that I was already beginning to feel it. The truth is that I went from fear of my first experience here to immediately feeling supported and feeling that I was in a safe space.

There was a moment when I wanted to let go of the camera and join, to shout slogans, to shout that personal feeling a bit, no? But I said no, I think it is important that I too can take a little of what I am feeling, which was above all a lot of emotion and a feeling of support and shoot. Every movement I made there was a woman holding my hand or opening my way, allowing me to move to one side, or to the other. There was a first moment in which I climbed onto a mobile home that was out there the whole crowd passed by and cheered us on, because most of us who were taking pictures were women, so that filled my soul a lot because it was kind of nice, they were also supporting us.

Mariana: Thank you very much, Delia. I was not at the march but I remember watching the coverage from afar and that feeling that you have, I listen to it again and it gives me goosebumps because that energy was transmitted in everything that people were uploading online. And I imagine you, I can almost see you with your camera and moving among the people and with that energy that you have– surely you transmitted this confidence. I remember and I even feel like crying, it is very beautiful. And thanks for sharing that experience. I would very much like to go back to something that you mentioned at the beginning: you mentioned that you wanted to go to this march because you felt the need in the depths of your being and you also mentioned a bit about your experience as being a woman living in the State of Mexico, then I would like to connect these ideas, that you tell us why being a woman living in the State of Mexico creates this need in the depths of your being to attend such a march.

Delia: As a woman from the State of Mexico, you learn to be valiant, and there came a moment in my personal growth in which I realized that being valiant all the time was not natural. I can talk about my experiences of violence in my commute, I am able to recognize these, and speak to them, I can identify an incident from every single time I have gone out. I have begun to understand that I live in a space that was already violent but also all the circumstances that exist here are double in violence because one is a woman. So, in the State of Mexico, we live many things, there is a lot going on, I have always believed that the people from here are very hardworking people, they are very insightful people, very noble people, but we are also, because of the context, we are the relegated city, like cheap labor that comes and goes from the city, because it cannot stay in the city, because in the city there is all this gentrification that is already very accentuated. So then we end up being part of the shore, and of the part of what we call a dormitory. The State of Mexico is like a kind of dormitory where people only get to sleep, where people do not really live their day to day, they only come and go. So because of all these contexts with which I have lived since I was a child, until today, I have reached a degree of understanding in which I have a lot of esteem for the place where I live but I also have a great desire for the context to be visible. Because it is very famous for being violent, for having the highest statistical index of femicide, of violence against women… and yes, it’s true, the statistics don’t lie, but there is also the fact that the State of Mexico is allowed to be a territory in which these things happen, right?

It was very important to attend because there was this event that happened here. I think that from that event on, I understood that we live in a context of violence, especially those of us who live in Ecatepec. I live in a neighborhood called Jardines de Morelos and about two years ago, a well-known femicide took place, here two blocks from from my parents’ house, and it was a national event because it was not a Femicide, there were about ten, from this couple that, well, it’s not worth even giving them so much weight, it was simply something that happened and I lived it. I went out here to the streets and they were … the corner of my parents’ house was full of, well, these tapes that prohibited the passage, a vacant lot was full of all these tapes, patrols everywhere, the news talking about all this, all the the streets around were filled with the media, with curious people. And so I was very shocked to see that in the corner of my parents’ house they found the bodies of several women, so for me that marked a before and an after of how to connect that fact with me, with my personal anecdotes of violence or harassment and to see that in the neighbourhood we were all affected and to see the relatives of these victims, and I did not know them but they were neighbors, and they were extremely devastated. It was a very strong event that I … for me it was an impact in which I said I cannot believe it. I felt violated, because although I did not know them, the event happened in a nearby space, a space like my home. So it was like a connection between that and not normalizing these events, like, I remember hours to go to Mexico City and many things happen to me on those journeys, so all the time I travel with fear, travel with uncertainty and then there comes a time when you feel very tired. So these are my needs and motivations as a woman in the State of Mexico… from my personal side, that’s why I went to the march.

Mariana: Thank you, Delia, for telling me this, I know how difficult it can be and I thank you very much for sharing it with us in this interview. I would like to go back, take a leap from what we are talking about right now, to the first question, and I would like it if you would tell me about this group of photographers that was formed.

Delia: The #Metoo movement opened a space for women photographers to form their own group because the truth is that the photographic community is very macho and also, that community is mostly formed by men, so it is difficult to find a space in which we can really feel protected, heard and not judged. So stemming from this, women photographers of great renown, history, and career formed this group, they invited women photographers from all over Mexico to join us and we had the first convention in, Mexico City and at that convention, we talked about all of the cases of violence that we had suffered in this field and we all spoke of the thousands of examples, of all our experiences, in agencies, in the media, in editorials, in anywhere where a bad experience could have taken place: from harassment to being threatened, to being asked to change jobs. The truth is that it was impactful to listen to them and so, from this instance on, it is a space in which now we work in flanks, that is to say, that with events like these we are monitoring ourselves, here we can upload material, we send each other announcements, if there is someone with whom we have the same internal complaints, we share information about it.

Mariana: Thanks, Delia. I believe that these spaces in which we share with other women and especially women who do what we do, help us to find and recognize ourselves and although the experiences are not always pleasant, knowing that someone else went through a difficult situation in a work that is shared, it makes it so that we can recognize these experiences ourselves and say it’s not right. Such a support network is very important, so it is very painful that these groups are born on the margins of these situations but at the same time it is assumed that these situations are so vulnerable that it makes us organize ourselves, that we build these infrastructures that help us to to get out of these situations, then radical empathy, radical support is born and I am glad that you have found this space within your profession. For my next question, I would very much like to talk about your photos, because during the first answer you talk about the energy that surrounded you, how you felt supported in this sea of women who went out to the streets amid slogans, and I connect it with your photos, with what you made us feel like we were there. I would like to ask you if there is any specific photo that you remember when you took it, and what you felt.

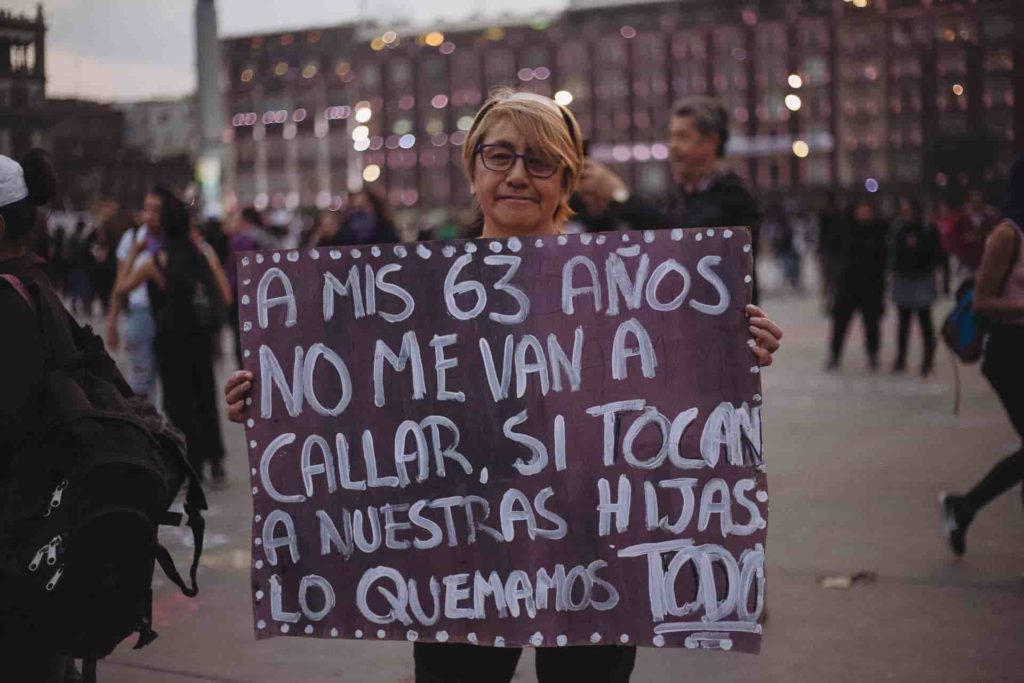

Delia: I think that all the photos themselves have a reason and a context. Above all what I most wanted to show, was the impact of what I was seeing, the number of women with multiple messages and slogans, with multiple messages of support for one another, women from all sectors, girls, mothers, young people, it was a moment in which there really was an opportunity to come together for a single reason and for the same feeling and those first images where you see the monument in the background and that sea of people is the first thing I remember.

Then, I focused on taking photographs of each of those girls that I saw with so much…force, with so much emotion, all of them looked … It was a mixture between overwhelm and happiness because it was a really exciting moment and then I focused a bit on the strength that I saw in them, I saw a lot of strength, I saw a lot of desire to express themselves– a rare occasion.

And then I focused on making them look like I was seeing them, it was important to represent them as the warriors that they were being at that time, for many of them it was the first time, for many others it was maybe their second or third but it was important to be there, others were accompanying others and it was also important. So for me it was very important to represent them, but also not to violate them, I tried to be careful, I tried not to take such frontal portraits to try to not be so detailed, but at the same time I tried to show that energy and that fierceness.

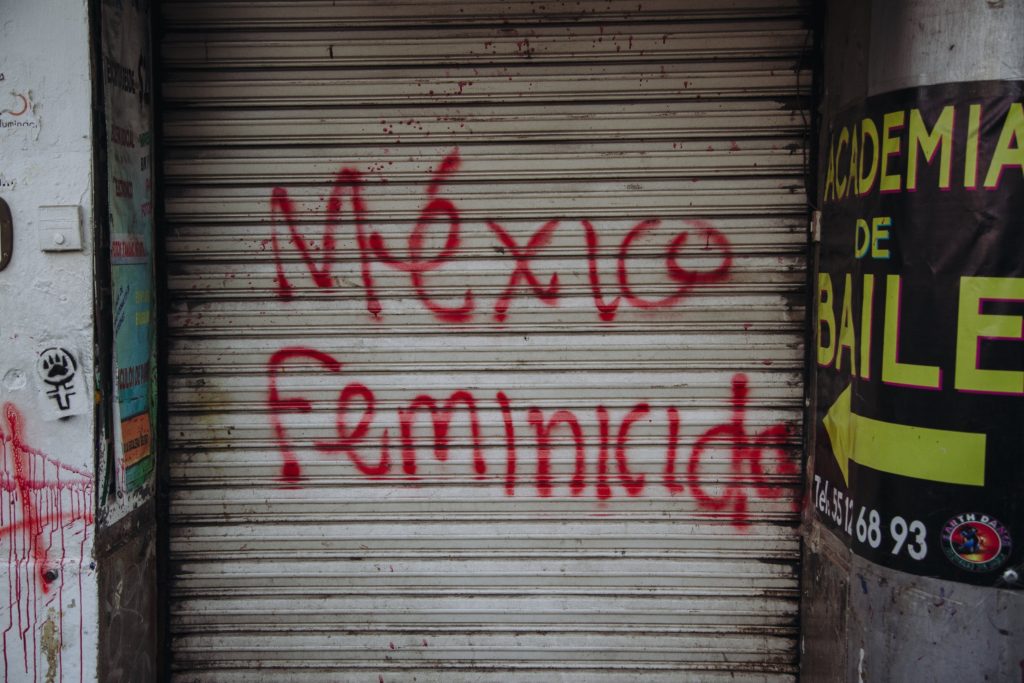

When I started to move forward, I started to find the part that is a little more violent but that is also very fierce and very significant. It is that part that is always sacrificed in the media because it is the one that receives the harshest social criticism. That just because they are women painting because they are women breaking because they are women hammering because they are women half-naked, they are criticized more harshly because “they should not do that”. I tried to take their photos but in a way that they do not feel like aggressors, I was trying to make it fair to make a contrast of what that moment meant for them. It seemed that they were having a kind of catharsis, that’s what I wanted to show more, a catharsis.

I decided that it was important to get to the plate of the Zócalo and continue capturing moments of these goosebumps that we all had. And I think that one of the moments when I was more moved was when I arrived at Bellas Artes because there was a temple where women voluntarily went up to tell their experiences of abuse and I stayed only for 5 minutes but those 5 minutes were enough to hear one of them, and her case was so strong that I lowered the camera and I started to cry, and around me there were many women crying and saying incredible things of support to that girl on top of the temple, while she recounted her experience of violence which was horrific. And then I raised the camera again, I wanted to capture this sisterhood, this support that is being experienced at that moment and that was when I took that photograph of a girl crying. It was important for me to show that the march was not only billboards, they were these moments of understanding, of support.

Mariana: Thanks, Delia. When I hear you narrate the “behind the stories” of your photos, I can see it and when you say that moment a girl who was crying, I can see it because of the strength of your photos, they remained recorded in my head, and I think it is an honor to be able to hear how you lived them, what happened, how you moved through the march and why. I also think that, well, it is important to mention that this is evident all the time in your work: the dignity with which you treat the people you are portraying, how your work stops time and you capture it. It is an honor for me to be able to listen to it too.

I would very much like to know if there is something that I have not asked you, that you consider important, that you think should be part of this story and that you would like to tell, or something that you would like to add.

Delia: I would like to add that we let it be known in the general community that we were inviting men to not attend the march. From the perspective of a photographer I saw a lot, I saw many invitations for men to not go, to please not, for the first time ever to not seek to be protagonists. And the only thing I can add about that is that there were men, men trailed behind, some were accompanying women, whole families went, there were male photographers taking photographs. There was a kind of agreement but it was not achieved for the most part. There is still a lot of work to be done, but I can say that something was achieved, which was the fight for a space in which we really needed to be alone as women. So that seems important to me to highlight, it was almost achieved, not in its entirety but there was a call of action and one which at times was respected throughout the march.

Another important thing to highlight is how people and workers who could not join the march because they were working, were waitresses, quartermaster personnel, passers-by’s, many, many, many women from their jobs in the buildings, on the street, would lean out and show their support waving their handkerchiefs. It was that second moment where I cried because we were there for them too, because many of them couldn’t be at the march and that they wanted to, and to see them take a break from their work, go out and .. And give some of us water or simply show a little flag and yell at us to continue, that they supported us, that … that they demanded justice, which demanded “not one more,” it was impactful, to see them, and it was very important, because they are also omitted and it is true that sometimes it can even be a privilege to go to manifest. But they were there symbolically.

Another moment was at the end when I managed to get on the Zocalo, there, there was already an ecstasy from the experience that we were all living, being able to take the space for ourselves, being able to feel it as ours, for that day, for that moment, to be able to do what we would like in that space, safely, and shouting. I saw all of them with a very strong desire to express themselves and that was like that second part of the coverage, the whole part of demonstrating the slogans, that part of strength, courage, the courage of many of them to be there and to do symbolic acts, being able to feel free, to take off one’s shirt, to take off all one’s clothes, to paint oneself, to be free, at that moment I felt them all free. It was a culminating moment to be able to say: yes we can demand justice, Yes we are supporting each other, yes we can seek that we have safe spaces, yes we can help each other, yes we can demand, yes we can raise our voices, yes they have to listen to us, they have to support us. Then, I portrayed those images where they, in addition to all this ecstasy and freedom, they made these circles in which they danced. There were groups of girls who danced on one side, others who brought drums and did a kind of celebration. They made bonfires and the fire also became a symbol, a symbol of the warrior in us and the war against everything that implies patriarchy in our society, the machismo. That fire was a symbol of burning many things that, as women, have drowned us and is drowning us. I saw all those women with a deep need to feel free and to be able to burn all those feelings of pain, those feelings of exhaustion, of silence, of repression, that they have lived. The fire meant union, a communion for them, it was a union.

Another thing that I would like to comment on, is that I never suffered, though there were situations where there was gas, where there were firecrackers, where there were things of that kind, I was very close to those situations but nothing more happened because the Marabunta brigade was close all the time, so they were intermediaries as always.

Mariana: Ok, Delia. I appreciate this. With this we end our interview, it is an honor for me and for the collaborators of this edition to be able to count on your experience, with your story and it gives me many feelings because I know many of the situations that you mention, I can feel them because I know how that is. And your narration transports me to Mexico City, to the plate of the Zócalo and although I was not there, your photographs appear in my mind.

To close our interview I would very much like to say that Delia and I were collaborators for several years in Mexico and thanks to that collaboration we became very close friends and it is an honor to always be able to talk about your work.

Delia: Thank you very much, Mariana.

Mariana Sanson is a multidisciplinary Media Studies graduate student and a producer of big-scale projects in media arts with a social approach and a human rights perspective. She has experience coordinating teams focused on the culture industry and civil society. A firm believer in non-fiction and the creation of media as a tool for social change and their impact to create collectivity.

Delia Martínez was born in Ecatepec, State of Mexico in 1987, studied Design and Visual Communication at the FES Cuautitlán, UNAM, from 2005 to 2010. She specialized in still photography, which she has practiced for 10 years as an independent professional. She has worked as head of the Photographic Registry area of film festivals since 2012 and made still photography for political campaigns and books on the construction of film audiences in Mexico.

1 thought on “Somos las que no se quedan calladas/ We are those who are not silent.”