Diamonds in Sierra Leone. Coltan in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bananas in Colombia. What do these have in common?

Some of the world’s largest conflicts are strengthened by the monopoly over these natural resources (yes, even bananas). Unfortunately, these natural resources are often seen, not as gifts of nature, but economic resources that can be harvested for personal profit instead of community and national development. Because of this value, many innocent human beings have been caught in the middle of the crossfire between multiple rebel groups fighting to gain monopoly over the extraction and distribution of such resources.

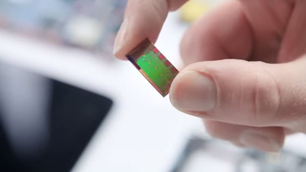

Minerals like coltan, gold, tantalum, tungsten and tin are rigorously mined and used in microchips found in most common electronic devices such as cellphones, cars, and computers—innovations enjoyed heavily by our generation. These are also conflict materials or hot commodities that have been one of the leading causes of mass atrocities and enslavement by armed groups in countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In fact, those who work to mine these materials gain little to no benefit from these resources. Profit derived from the sale and distribution of these materials often fund armed groups’ campaigns of human rights abuses.

At a panel entitled “One Year Later: Progress in the Pursuit of Conflict Free” at this year’s Social Good Summit, Intel CEO Brian Krzanich promises Intel’s intent to be “Conflict-Free by 2016.” What does it mean to be “Conflict-Free” and how does it promote corporate social responsibility?

This means that the company intends to completely diminish the use of conflict materials in their supply chain. Intel’s promotion of responsible methods of sourcing conflict-free minerals as well as its support for conflict-free mines and its role in encouraging others in its network and in the industry, such as Dell and HP, to do the same shows its devotion to corporate social responsibility. Instead of simply retreating from the problem in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, they are trying to fix it. “Fix it for good,” says Krzanich.

Krzanich was joined in the panel by student activist, Roxanne Rahnama. Rahnama, an undergraduate student in the University of California, Berkeley, became involved with Conflict-Free Campus initiative (CFC). CFC hopes to ensure that colleges and universities do not use or purchase electronics made of conflict-minerals. Her work as a student activist is inspiring and to date, 17 schools have already committed to ensuring that their campus’ technologies are conflict-free. Rahnama says, “Technology, if managed responsibly, can be a bigger force for social justice.”

We must not leave the pursuit of conflict-free materials solely to corporations. Instead, responsible consumers should complement their work. As consumers, what can we, as global citizens, do to contribute to the campaign to use conflict-free materials? While we may not have the capacity to actually work on the ground, it is possible for us to raise awareness and educate others about the use of conflict minerals. We can also try to elicit change in our own communities by encouraging others to become more responsible consumers by getting informed about the products they are using. By doing so, we are joining corporations, like Intel, and initiatives, such as CFC, in solidarity towards a conflict-free tomorrow.