If you’ve ever asked yourself who on earth still uses internet forums or user groups, the unlikely answer might be Somali people. Every Somali child growing up in the diaspora remembers the popularity of websites like Somali Net, Somali Spot, and Somalia Online. I spent many summers in Seattle scrolling through long personal posts on those forums. Those message boards often felt like my only connection to a country I had little in common with anymore. Not for nothing, the writer Najma Sharif notes that Somali people have used the internet “like an extension of the motherland, connecting millions of Somalis to one another.”

The Somali Net forums were known for wild stories that would spawn hundreds of pages of comments. One of the most infamous was a story written by a Somali-Canadian girl who chronicled her dhaqan celis experience; essentially, a practice where western-based Somali parents send their kids back to Somalia with hopes of keeping them out of trouble.

Some Somalis, especially the younger crowd, are also active on more popular social media like Tumblr and Instagram. Even the archaic Facebook is home to a number of groups each focusing on different aspects of Somali life, like Somalis in Tech, Somali Expat Forum, and Mixed Somalis. However, Twitter continues to be where the largest contingent of Somalis congregate: a quick search of the tags “Somalia” and “Somali” yields tens of thousands of results showing Somalis sharing memes, debating the motives of Turkish aid, or correcting tweets that wrongly refer to Somali people as “Somalians.”

While the Somali diaspora is spread across continents and different social media platforms, making fun of outsiders has always been a great unifier.

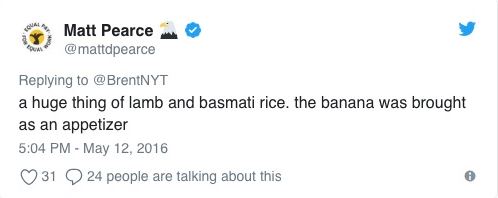

In a now infamous tweet, Matt Pearce, a correspondent for the Los Angeles Times, dining at Maashaa’allah Restaurant in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood in Minneapolis, shared a picture of an enormous plate of Somali food. The picture showed rice, lamb, a salad and a banana to the side. The banana, Pearce claimed, was an appetizer. However, the banana was meant to be eaten with the meal. Pearce would quickly find out–via social media–about his faux pas and just how serious Somali people are about their cuisine.

Lucas Peterson, a correspondent for Eater.com’s series “Dining on a Dime,” discovered the same. Last March, Eater.com posted a Youtube video, “Somali Food is the Best Cheap Meal in Chicago” where the host visited a Somali restaurant on Chicago’s north side. In the video, Peterson make two basic mistakes: He called Somali people ‘Somalians” and he mashed up the banana (that was meant for his lunch meal) with his laxoox, a type of Somali breakfast pancake. Once again, Somali people on Twitter and Facebook united to ridicule this Westerner for not having researched Somali cuisine before making a video about it. What’s worse, his host did not correct him. While Peterson did not address his mistakes, Matt Pearce would go on to write an article for the Los Angeles Times about his experience.

NBut not all online discussions of Western media engagement with the quirks of Somali culture, are negative. In January 2018, NPR reported on a viral dance trend started by a Somali comedian’s music video. The song, “Barbar” (Somali for sideways), appeared both a comment on love, but also referenced Somali resilience. Then there’s the Somali tradition of rude nicknames.

Still, media representation of Somali people is rarely so light-hearted. Often cited as the leading example of a failed state, Somalia has struggled with security problems ever since the ousting of dictator Mohammed Siad Barre in 1991. The mid 2000’s saw an increase in pirates attacking ships off the Somali coast, eventually spawning a Hollywood movie. In October, a truck bomb in Mogadishu claimed over 400 lives and injured thousands more.

News coverage of Somalia tends to fall into many of the same clichés as Hollywood movies. A Forbes article meant to be about Somali multi-millionaires instead begins with the sentence, “Somalia, a failed state in East Africa…”. Other news outlets continue to rely on dated images of Somalia. While CNN and BBC were writing about Somali pirates, Somali Agenda and other Somali news outlets reported on overfishing and nuclear waste dumping by the West, both leading causes of piracy.

This is all to say that Somali people have always been best at telling their own stories.

Amongst memes, gifs, and the internet’s flippant nature, Somalis have found a way to create their own narratives. A space where the phrase “failed state” is only used to insult someone’s hairline, and where viral hashtags like #finepeoplefromsomalia are used as an opportunity to showcase Somali beauty.

Hamda Yusuf studies international relations and media at The New School in New York City.