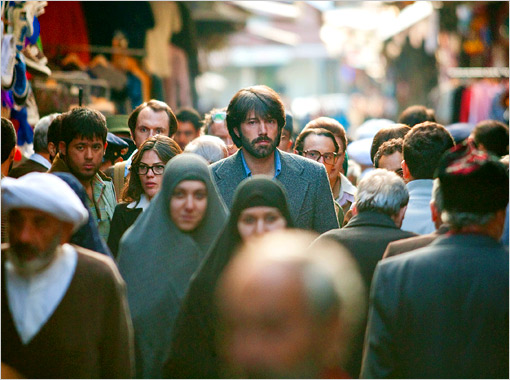

Argo, a suspenseful tale portraying America’s favorite bad guys, Iranians, as angry gun-toting religio-fascists, just won the Best Picture Academy Award for 2012. Ben Affleck’s directing is better than his acting, but this was not a character driven movie—it was made because it was based on true events. During the Iranian student takeover of the US Embassy in 1979, six embassy workers escape to the Canadian ambassador’s home and eventually make it onto a commercial plane with the help of the CIA and the Canadian government. The remarkable story is pumped full of cinematic and narrative steroids to create a marketable movie.

Argo, a suspenseful tale portraying America’s favorite bad guys, Iranians, as angry gun-toting religio-fascists, just won the Best Picture Academy Award for 2012. Ben Affleck’s directing is better than his acting, but this was not a character driven movie—it was made because it was based on true events. During the Iranian student takeover of the US Embassy in 1979, six embassy workers escape to the Canadian ambassador’s home and eventually make it onto a commercial plane with the help of the CIA and the Canadian government. The remarkable story is pumped full of cinematic and narrative steroids to create a marketable movie.

This is not a critique of Argo per se—as everyone seems to agree, it was well-made. This is a swipe at the lack of vision from its left-leaning, politically active celebrity actor-director (Affleck, who also produced along with George Clooney, could have gotten a more relevant and risky movie made) and the Academy’s rewarding of Americana, disguised in the beginning but glorified by the end. It is also an admission that studying international relations and the sins of the United States can cause one to see unchecked pro-US propaganda everywhere. But at a time when our government continues to train its citizens to see Iran as nothing more than a hostile enemy, do we need a film like Argo further demonizing its people—while championing the CIA!? Not to downplay the hostage crisis at the embassy, but no one suffered as dramatically and totally as the Iranian people following the Ayatollah’s revolution. (After all the hostages were freed, Washington then backed Iraq’s Saddam Hussein as he began a devastating eight-year war with his neighbor.)

Django Unchained gave some historical context (read: horrors of slavery) to Lincoln, and Zero Dark Thirty, which also has a conflicted CIA agent as protagonist, provides a similar contrast to Argo. Both are inspired by documented acts of US foreign policy and hyperfocused on the specific results of high-level government decisions, providing a rare insight into top-secret procedures. The similarities diverge as Argo slowly extracts the storybook silver lining, complete with its white male hero, out of an epic US-led catastrophe. The 1953 Mossadegh coup and the American coddling of the corrupt, authoritarian Shah were touched upon in an odd historical film reel at the start but promptly dismissed. The film ignores the overall hostage-crisis context and offers the Orientalist concept of the most easily palatable villain, the Other. Zero’s complexity underscores Argo’s safe, historical cherry-picking.

While it is true that many parts of Iran were unstable and marked by violence during and immediately after the revolution, almost no effort is made to provide sympathetic Iranian characters. They are all fanatics and Iran is a giant prison of armed guards and angry mobs—a necessary cinematic conceit to create claustrophobia and tension. The movie only works if the audience is afraid of Iranians, even women in their all-black chadors have guns, and that is a problem.

Where Zero eschews the W. Bush–era Manichean West vs. Middle East template and instead highlighted the moral vagaries on both sides of any extended interstate conflict (cold and hot), Argo celebrates a shaggy bureau bum version of James Bond and the universal appeal of Hollywood, which comes to the rescue. Though Zero has the natural pro-Western biases of any movie made for Western audiences, the hubbub over the efficacies of torture proves that the film is not only relevant, it is an unapologetic assertion that America’s warrior class do not hold the moral high ground. Argo has been touted as illustrating that clever nonviolent solutions can work in terrible situations—a message that would have been much clearer if the story were set against the military’s disastrous helicopter rescue attempt (given a brief mention). But to its credit as a movie, the script is tight and doesn’t allow for subplots. Yet in the last ten minutes, that compactness unravels into a triumphal score introducing a sentimental denouement—and backslapping at Langley that mocks the long-list of atrocities committed by the CIA in the region from the 1950s on. The Agency comes out smelling sickly sweet.

Of course movies are primarily entertainment and do not require high-brow takeaways or disturbing, relevatory truths. But awarding the Best Picture Oscar to a movie that serves to justify the US’s belligerent stance toward Iran, only the most simplified and misunderstood of Washington’s many Frankenstein’s monsters, can certainly be seen as propaganda (as well as self-idolization by the same old Hollywood voters that chose The Artist for 2011 Best Picture).

Argo serves to reinforce stereotypes of Iranians as nothing more or less than America’s most reliable foes. It is Miracle—the Olympic feel-good film that vilified the Soviet Union to lift our spirits during those dark times before Ronald Reagan saved America (Rocky IV offered a less one-sided perspective)—without ice skates or character development, but with the same happily ever after.