On the morning of August 9th, I awoke disoriented to the distant, muffled sound of song. Wiping the grogginess from my eyes, I thrust my heavy blanket towards the foot of the bed and was immediately enveloped by crisp highland air. The chill was a reminder I had chosen to trade the sticky summer heat of New York City for the formidable winter of Lesotho, the kingdom nation in Southern Africa where annual snowfall is not uncommon. I was in Lesotho for The New School summer session to do research for my thesis, which is focused on the construction of national identity in Lesotho through the establishment of a new national museum. I had chosen to research the museum in Lesotho based on the connections I had established in the country over a number of years; first through Peace Corps service, and more recently through collaborative co-management of a literature festival there called Ba re e ne re.

The singing was getting louder.

Kicking on my slippers, I had a flashback to earlier in the week. I was walking down Kingsway, the central thoroughfare of Lesotho’s capital city Maseru, when I spotted a poster of the Sunday Express newspaper that had announced,

I wondered if the singing could be from the striking workers. In order to keep my expenses low over the summer, I had eschewed the conveniently located neighborhoods of near central Maseru and instead rented a modest apartment situated a ways out from town. The area I ended up in was called Masowe 1, which is nestled amongst a series of peripheral suburbs (including Masowe 2 and Masowe 3) to the south of Maseru. Nearby, a little down the road from my house, was a massive industrial complex. I knew that within the compound sat a cluster of factories dedicated to the production of textiles and lightbulbs.

The singing blended into chanting, then flowed back to singing as it marched closer.

Not wanting to miss the activity, I threw on my clothes as fast as I could and burst out into the street just in time to see a mass of several hundred people passing by, claiming both sides of the road as their own. Assessing the situation, I saw the crowd appeared to be mostly working class women dressed in ordinary clothes. This strengthened my theory about the group representing striking workers. I approached the group with cautious excitement, and asked a marcher if this was indeed a factory strike. She quickly confirmed, proclaiming, “We are striking because we need chelete.”

Chelete means money in Sesotho and factory workers in Lesotho do not earn a lot of it for their long hours and repetitive tasks. Nearly all large factories are owned and operated by Taiwanese and Chinese people who have settled in Lesotho over the course of the last couple decades. Navigating a landscape of trade agreements in the globally competitive textile industry, factories have ended up in Lesotho to circumvent national production quotas (through what was the Multi-Fiber Arrangement) and benefit from trading preferences such as those currently offered by the United States’ African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). While the factories have created jobs, the wages they offer are hardly livable. At the time of the strike, factory workers could earn a minimum wage of about 1238 Maloti (about $85) per month for full time work, where full-time can mean 12-hours shifts, 6 days a week.

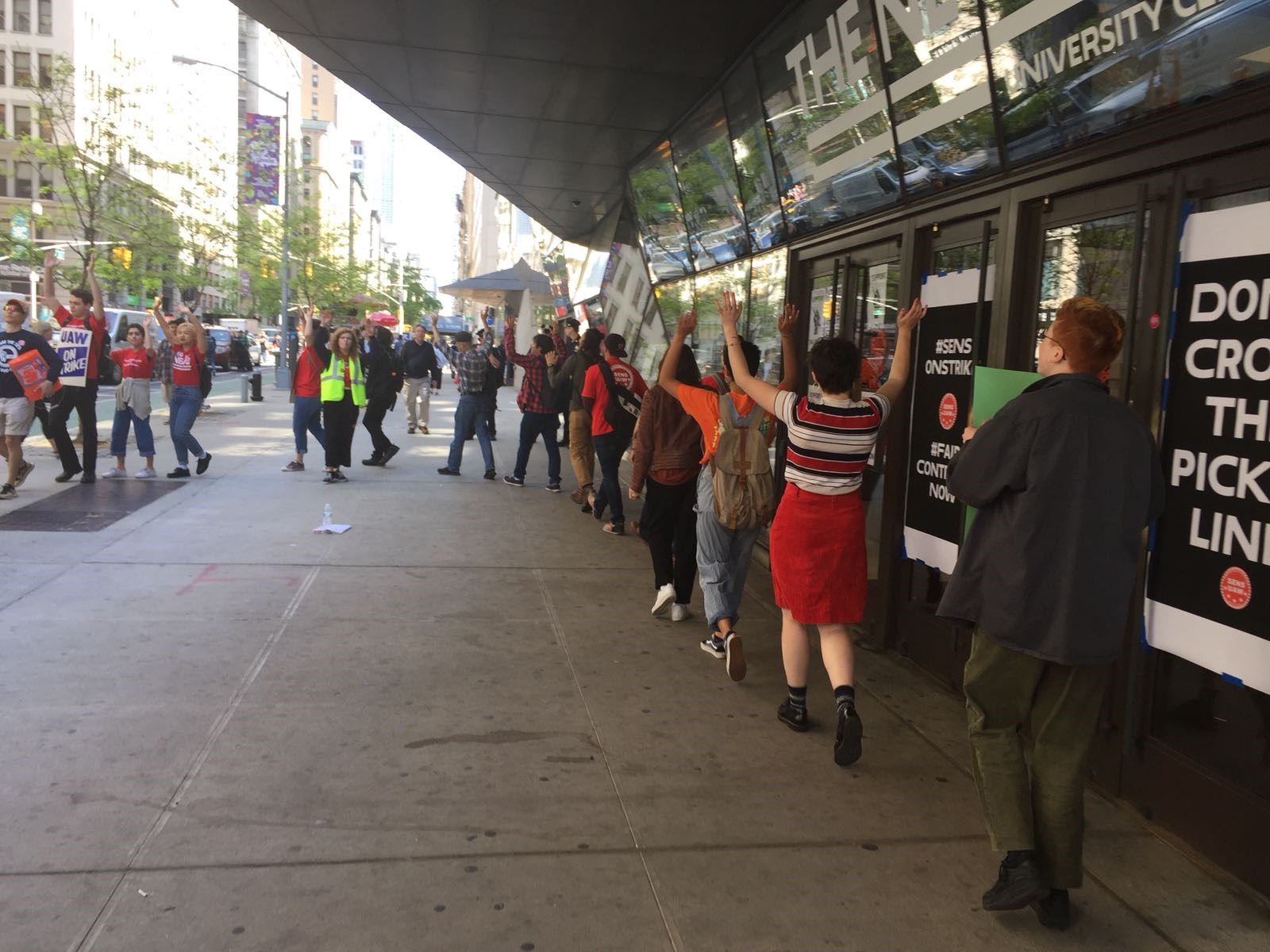

Having recently gone on strike myself as a student worker at The New School in May, I was filled with a sense of solidarity as I joined the crowd in marching towards Maseru. Women ululating and singing while waving freshly broken boughs reminded me of forming picket lines with colleagues in the Student Employees of the New School union (SENS-UAW) on 5th Avenue, 12th street and 16th street, sharing protest chants and waving placards. Chatting with more factory workers as we marched I learned that key motivations for the strike were the recently announced taxi fare and utility cost hikes. All this while the Prime Minister of Lesotho, Thomas Thabane, had yet to fulfill a campaign promise to raise wages to a new minimum of 2020 Maloti per month.

Marching onwards, the workers continued to block all lanes of traffic, leaving large rocks on the road in their wake and ensuring the memory of their actions would be remembered even beyond their presence. The disruption elicited mixed reactions of support and frustration from various drivers meeting them on the road. Every time a car was forced to reverse and turn around, a roaring cheer would roll through the crowd. After progressing a couple of miles towards town, a police van materialized ahead. Officers disembarked with helmets and large rifles to establish a police line and derail the march. I shifted to the margins among the onlookers from the surrounding neighborhood and observed as the workers, unfazed, boldly pushed the line. Women were the bravest, some theatrically throwing themselves to the ground and rolling beyond the threshold established by the police. Fortunately, the police showed some measure of restraint and did not rush to physical violence. However, as more time passed with the workers refusing to back down, the police officers lost their patience and eventually fired tear gas into the sky. The loud eruption of the gas canisters leaving their chambers and the arches of their descent caused the crowd to scatter with people running down narrow dirt paths and through yards adjacent to the main road. The police held the street for a little while, and then boarded their van to drive away. Evidently, workers in another area of the city needed responding to as well.

Before too long several modest sized groups of workers had coalesced again with chanting and protest songs alternating afresh. I joined them as they penetrated further towards the city center. Soon we arrived at the open sports fields where workers from the Thetsane industrial were confronting a new police line. Rocks covered all the roads and black smoke rose from burning tires in several places. The workers demanded to be heard and they had been successful in bring their factory floors and many of Maseru’s streets to a standstill.

Yet, more pops of tear gas followed, helicopters flew by overhead and larger military vehicles were spotted in the distance. A light rain fell as the workers dispersed in clusters into the neighborhoods, still singing. I finally broke away and headed the rest of the way into town, noting that burned tires metamorphose into charred piles of thin elegant rings.

I followed the subsequent reporting of the stikes in local newspapers very closely. It was remarkable to observe the political slant of the various papers by seeing how the strike actions were characterized. In some articles the workers were described as riotous mobs intent on destroying property, while in others the meaningful fight for a living wage was acknowledged. Regardless, the stikes had made an impression in the public consciousness and forced the government to address the workers’ demands. Initially, the government seemed prepared to take steps to officially raise the minimum wage to 2000 Maluti, yet soon backpedaled and delayed making changes. The inaction ignited further waves of protest over the next few days. Negotiations continued however. By late August the workers had won, with the government agreeing to the 2000 Maluti minimum wage. Though still a modest monthly income, the 62% raise that came as a direct result of sustained collective action from the workers is a remarkable achievement.

In Lesotho, the economic environment for industries tends to be very fragile. Concerns are common about the possible departure of foreign investors who provide many formal jobs in the country. Especially in the globally competitive textile industry where there are many service providers internationally and consumers are very price sensitive, businesses threaten the importance of keeping wages low and productivity high for retaining jobs. Yet the Lesotho strikes showed that through powerful collective action, workers can be successful in improving their conditions.

Reflecting on the strikes in Maseru and the campaign for the first student worker union contract at the New School, I thought about how much labor struggles have in common. It was beautiful to witness the unique, but resonant cultures of social action in each place. From the singing, to the marching, to the symbols and messages of protest, in each place workers stood together to advocate for their demands. In each place large institutions balked and tried to beguile their communities, yet ultimately, in each place the collective resilience of workers has been and will be triumphant.

Zachary Rosen is a current student of International Affairs at The New School, as well as a contributing writer and member of the editorial board of Africa is A Country.