Each summer, students from SGPIA spread out across the world as part of the International Field Program (IFP) and Studio Programs! Students conduct independent research, contribute to the vital work of local non-profits, NGOs, and government agencies, and gain invaluable international experience. This summer, our students are living, working, and learning in Argentina, the Balkans, Colombia, Cuba, Ethiopia, and South Africa. The IFP and Studio Correspondents will be the eyes and ears in the field to help us tell the stories of the summer. Check back to learn about each of the field sites.

My time in Cape Town is coming to an end – I can’t believe it! Two months have really flown by. Our final two weeks of our internship with SDI have been really busy tying up the loose ends of our projects. We’ve been preparing a presentation of our work on the reports for the Liberian data, and I have been preparing a social media presentation for a KYC.TV Youth Exchange happening next week, where youth from federations across the continent will come to workshop and share ideas for how to expand KYC.TV programming. Visit their YouTube channel here, where you’ll find videos created by youth participants.

When I’m not working, I’ve been reflecting on my time here, writing and sending postcards, trying to squeeze in any last minute activities before saying goodbye to this place that’s been a huge source of inspiration and contemplation for me.

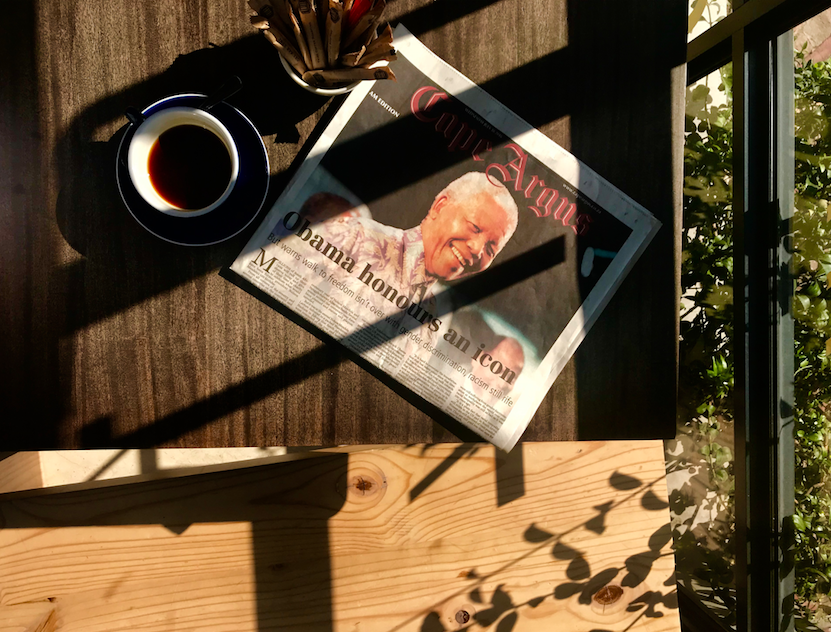

I’m writing to you on Mandela Day – a national holiday dedicated to service on Nelson Mandela’s birthday. Today he would have been 100 years old. Yesterday, on July 17th President Obama gave a speech at Wanderers Stadium in Johannesburg, at the annual Mandela Foundation Sponsored celebration. 15,000 people attended the event, and while I’m sorry to have missed it in person, just to have been in the country during such an historic time feels humbling beyond words.

Reminiscent of so many of his presidential speeches, Obama spoke of hope, of our changing times, and of staying the course in the wake of uncertainty. His prose eloquently wove its way between stories of heartfelt personal anecdotes and the state of our complicated global affairs in the way it seems only he has perfected. Honoring Madiba’s legacy, he shared his personal inspiration won from the legendary activist, admitting the same cause he fought for while locked away in Robben Island was a cause for inspiration for the young Barack, setting his course on a political path. But he also warned of changing times, of the times ahead, and of being aware of the politics of this era:

In fact, it is in part because of the failures of governments and powerful elites to squarely address the shortcomings and contradictions of this international order that we now see much of the world threatening to return to an older, a more dangerous, a more brutal way of doing business.

Although it has been 5 years since his passing, Mandela’s face is seen all over the country; in murals, on t-shirts, in traditional South African fabric, even on neckties. An homage to the great freedom fighter, ever present in his homeland. But on this day, and throughout my time here, I’m left wondering how his legacy is being honored in his society. Mandela fought for the freedom of his people. A political prisoner, he sat in confinement for 27 years, fighting against the inhumane injustices enacted by the Apartheid regime. His tenacity, strength, and steadfast commitment to justice in the wake of extreme oppression won him the title of the first Black president of a free South Africa. For what felt like the first time in history, a freedom fighter, unapologetically dissenting against the oppression of political injustice was successful in his fight. He instantly became an international champion for social justice. But how is that message still translated today, 24 years post-apartheid?

On our second week here, we visited Robben Island, the small island off the coast of Cape Town that has served as a political prison since the 17th century. Mandela was imprisoned in a 4 square meter (43 square ft) cell for 18 years on the island. Our visit was led by an ex-political prisoner who told us of the secret meetings he and Mandela and all of the political dissents held during their time in confinement. Meetings that would later reform the ideologies behind the ANC, the DA, and many other political parties.

24 years out of the brutal apartheid era, 5 years following Mandela’s death, only months after the ousting of former President Zuma on charges of corruption, and almost 2 years since his term as President of the United States ended, Obama’s visit has been overwhelmingly celebrated in the country. His message signified hope, change, perseverance, and an unwittingly optimistic outlook on life. His personably charming demeanor a source of great comfort to citizens worldwide, seeking a sense of solace in the post-9/11 era. While his foreign policies have been arguably status quo for many of his predecessors, for many Americans, his social policies were inspiring beyond measure. But following the 2016 election, and the many storied events that have followed in American politics, the idea of legacy remains a question for me. He continues by addressing the remaining inequalities present in the world, regardless of the advancements made in the last quarter-century:

So we have to start by admitting that whatever laws may have existed on the books, whatever wonderful pronouncements existed in constitutions, whatever nice words were spoken during these last several decades at international conferences or in the halls of the United Nations, the previous structures of privilege and power and injustice and exploitation never completely went away. They were never fully dislodged. It is a plain fact that racial discrimination still exists in both the United States and South Africa. And it is also a fact that the accumulated disadvantages of years of institutionalized oppression have created yawning disparities in income, and in wealth, and in education, and in health, in personal safety, in access to credit.

His address mirrors my exact feelings on the present state of South Africa, “In other words, for far too many people, the more things have changed, the more things stayed the same.” In this post industrial, post neoliberal era of heightened capitalism, economic inequality is a given in many places around the globe. South Africa is perhaps one of the most striking examples of this.

Throughout my time in Cape Town, and the surrounding cities in the Eastern Cape,economic and social inequality is shockingly apparent. Every major city we’ve visited in our time here has displayed some form of informal living environment. Far too reminiscent of the apartheid-era housing policies, many Black South Africans remain living in communities settled at the height of apartheid, with little access to basic amenities, proper infrastructure, and adequate housing. But this has become the norm. In Cape Town alone, one out of four residents lives in informal housing. This can qualify as anything from backyarders (homes built in the backyard of an existing home), to corrugated iron shacks. It is overwhelmingly the former. Huge, bustling communities are sprinkled around the outskirts of the city, with hundreds to thousands of unique, hand-built shelters, tightly fit together in communities often faced with innumerable location problems, environmental threats, and limited access to basic human and social services.

Since the end of apartheid, the number of households living informally in South Africa has actually increased. Proper statistics on these numbers is hard to come by. According the Housing Development Agency, community enumerations reports in 2011 found that 5% of households in the country were living informally. Where a report by StatsSA found that 13.1% of households were living informally the same year, 7,268,300 people. Discrepancies in data are common, given the slow housing policies enacted by local governments.

All of this to say that in the wake of my departure from this magical and mysterious place, given our current geopolitical climate, I’m left with a sobering contemplation of how the legacies of political dissidents fighting for social justice are kept alive after their absence. Mandela fought tirelessly for the equality of his people, yet so many of them are left in a predicament all too reminiscent of the one that was abolished 24 years ago. Obama fought for the social policies of minority groups who may have never anticipated reaching equality in their lifetimes, yet the current administration is doing everything it can to remove those liberties. I’m left wondering how social policy can be enacted in a way that is lasting, in a way that doesn’t leave the livelihood and well being of human populations in a precarious position, at the mercy of the whims of erratic figureheads.

Preparing to leave has been a somber experience. Cape Town is a beautiful and enigmatic place. It has a spirit that is reminiscent of many places I know very well – my hometown Detroit, especially – but its uniqueness is unmatched and something I hope is preserved while the city experiences its inevitable evolution. I feel I’m left with far more questions than I have answers, and I only hope I can return someday to dig deeper.