The people of Sierra Leone are to be commended for performing their democratic duty—in droves. On November 17, more than 2.2 million voted, almost 90 percent of eligible voters, and no serious violence was reported. Five days later, the National Election Commission (NEC)—responsible for Sierra Leone’s entire voting system, from biometric registration to counting—announced that President Ernest Bai Koroma of the All People’s Congress party (APC) was re-elected to another five-year term. Since Koroma received more than 55 percent of the ballots cast, the run-off election some anticipated was not necessary.

The people of Sierra Leone are to be commended for performing their democratic duty—in droves. On November 17, more than 2.2 million voted, almost 90 percent of eligible voters, and no serious violence was reported. Five days later, the National Election Commission (NEC)—responsible for Sierra Leone’s entire voting system, from biometric registration to counting—announced that President Ernest Bai Koroma of the All People’s Congress party (APC) was re-elected to another five-year term. Since Koroma received more than 55 percent of the ballots cast, the run-off election some anticipated was not necessary.

His main opponent, former military leader Julius Bio Maada of The Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP), received 37 percent of the vote while seven other presidential candidates split roughly 5 percent. Local races, from councilors and mayors to parliament seats, also comprised the election.

The SLPP leadership, which has traded political power with the APC since 1961, refused to recognized the overall election results and called for its winning parliamentarians and council members to boycott the government until an “independent international assessment” of the voting can be done.

This was a slap at the NEC and its apparent lack of interest in addressing SLPP complaints of election fraud—including charges of APC ballot-stuffing and vote-buying. The NEC has noted the complaints on its website, asking for the accusers to provide solid proof.

The United Nations chief observer Richard Howitt, who lauded the election as peaceful and transparent, acknowledged reports of APC bribery at several polling stations. But cases of tampering in some districts, according to Howitt, have been the “exception, not a trend.” The chief observer did admit that the ruling APC held a strong advantage in campaign resources and media airtime.

Indeed, the majority of English-language press outlets that cover Sierra Leone back the current administration —some more subtly (The Sierra Leone Times, This Is Sierra Leone) than others (Cocorioko, “Sierra Leone’s biggest and most-widely read newspaper”). The most outspoken English-language outlet supporting the opposition SLPP (that doesn’t formally bill itself as SLPP) has been the Sierra Leone Telegraph. (Read a critique of Sierra Leone’s media during the 2012 election here.)

But polarization in the Sierra Leone media—obviously exaggerated during election season, as in the developed world—only represents more problematic political divisions. Voting is generally done by blocs, not by individuals, who benefit from a patronage system that resembles the special interest groups of First World lobbies. From Think Africa Press

The APC draws majority support from the Temne, Limba and other northern tribes, and Krios of the Western Area, while the SLPP are favoured by the Mende and tribes of the southeast. Elections are regarded as “winner takes all” contests with defeat entailing exclusion and disadvantage for the losers, and their regions…. Both parties, when in power, have used their position to fund political campaigns and buy voters. This practice remains widespread. Political parties continue to organise and condone the intimidation of voters, often perpetrated by their youth wings.

Another problem for the frustrated SLPP leadership: Hundreds of international monitors were on the ground, from the European Union, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) as well as the African Union, the UN and the U.S. Carter Center—some observers had been in-country for months. The consensus? A free and fair election in Sierra Leone. The international community bestowed its legitimacy and the only group crying foul is the losing party—not a particularly objective group.

The NEC, an organization steeped in international money and credibility, is not concerned about the SLPP’s accusations—nor is it beholden to Sierra Leoneans. Ernest Bai Koroma was sworn in by the NEC the day after the results were announced, and he has been congratulated by the likes of President Obama, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and EU High Representative Catherine Ashton. The 2012 election is over.

Boomtown

In spite of its wealth of mineral deposits, Sierra Leone is one of the world’s poorest countries. In 2011 it placed 180 out of 187 on the UN Development Index, which ranks life expectancy (49), maternal mortality (970 per 100,000), income per capita ($340 a year) and adult literacy (41 percent). It is slowly creating an infrastructure—based almost entirely on foreign aid and investment—but roads, running water, electricity, health care and telecommunications are still relatively scarce. The average Sierra Leonean’s lack of education and skills limit potential of individual advancement and societal growth, particularly by Western metrics.

And yet according to Businessweek, Sierra Leone has the fastest growing economy in Africa.

Sierra Leone’s $2.2 billion economy will expand 21 percent this year and 7.5 percent in 2013, fueled by diamond mining and iron-ore production by London-based African Minerals Ltd. (AMI) and London Mining Plc (LOND), according to the International Monetary Fund [IMF]. Foreign direct investment soared to $3 billion so far this year from $200 million in 2007, Koroma said in an interview … on Nov. 10.

A UN Security Council report in August had the IMF projecting “extraordinary growth of 35.9 percent in gross domestic product in 2012” and a Chinese steel company pouring in $1.5 billion.

Earlier in November, a major US evaluator of good governance (to encourage public and private investment) gave the international community a new green light to do business in Sierra Leone. Freetown sent this press release:

The Government of Sierra Leone is pleased to inform the general public, development partners, civil society groups and the media that on November 7th 2012 Sierra Leone passed the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) scorecard for the first time since the international ratings initiative was established in 2004. The MCC is a United States government aid agency that gives funds to low income countries as a reward for good governance. The decision on which countries to give funds to is based on annual performance scorecards consisting of 20 indicators that measure social, political and economic issues.

This news was not picked up by the British press (who regularly cover West Africa), despite the fact that Sierra Leone did not pass the MCC score card in 2011. Perhaps this information didn’t gel with the media narrative, which hyped the election as tight and warned of political violence. The blurb-style coverage in the West rehashed the civil war from a decade ago and never went without the “Sierra Leoneans live on less than $1.25 a day” factoid. Meanwhile, Freetown had improved, within the year, in MCC categories including Freedom of Information, Girls Primary Education Completion Rate and Trade Policy—yet fell short in Natural Resource Protection and Inflation.

Though the mining industry has boomed, and oil exploration is looming, foreign industrial development has not improved the lives of most Sierra Leoneans. But there is potential for Chinese agriculture funding and hope that prolonged peace can build tourism. The promotion of the concept of free and fair elections has been crucial for private investment, which President Koroma is keen to get.

The NEC Goes International

Ernest Bai Koroma was an insurance broker in 2001—a smart businessman who took advantage of postwar restructuring to win the APC’s presidential nomination in a stunning 2002 upset. (He went on to be defeated handily by SLPP incumbent Ahmad Tejan Kabbah.) In 2007, as minority leader of the All People’s Congress, he defeated the vice president of the SLPP, which had been in power for most of the last decade (when not interrupted by coups).

The NEC played an important role in Koroma’s victory. Though a National Election Commission had been enshrined in the 1991 Sierra Leone constitution, the United Nations effectively made it over as an independent organization in 2005, disconnecting it from the national government. In 2006, Dr. Christiana Thorpe, a former government minister with an impeccable human rights résumé, was named Chief Electoral Officer. (During the 1991–2002 civil war, she was politically and socially active and helped found the Sierra Leonean chapter of Forum for African Women Educationalists [FAWE]. She received various international honors, such as the “Voices of Courage” in 2006.) An impartial, independent NEC, seen as above party loyalty and headed by a respected humanitarian, lent the Commission legitimacy going into the 2007 election.

The 2007 presidential election, not this year’s contest, was the true test of Sierra Leone’s national fortitude (despite the media’s natural inclination to exaggerate this November’s historical significance). Just five years after the war, it was the first election to occur without thousands of UK troops deployed. Buoyed by plenty of funding and technical support from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and international donors, Thorpe and the NEC saw to it that the election was given a worldwide stamp of approval as free, fair and generally nonviolent.

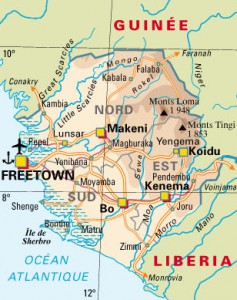

The peaceful transfer of power from the Sierra Leone People’s Party to the All People’s Congress in 2007 was a watershed in the nation’s existence. However, it was a controversial NEC ruling that put Koroma and the APC in charge. Implying ballot-stuffing and underage voting, Thorpe’s group announced the annullment of ballots in 477 polling stations where “instances in which greater than 100 percent turnout was reported,” in and around SLPP-held regions such as Kailehun and Kenema (see the National Democratic Institute report).

From one perspective, the action solidified the NEC’s status as an objective institution—after all, outgoing president of the SLPP, Ahmad Tejan Kabbah, installed Thorpe as chairwoman. That the NEC acted against the party in power could also be seen as adding to its credibility. The UNDP and the international donors were obviously counting on this view. The other perspective, held today by many in the SLPP, is that the NEC stole the election.

Thorpe was widely hailed for the successful election and won the 2009 German Africa peace prize, which augmented her reputation on the international stage. (Read an interview with her here).

To prepare for 2012 election season, Thorpe and the NEC implemented Biometric Voting Registration (BVR), which started recording fingerprints and faces in January. Critics, citing that a majority of Sierra Leoneans live on dollars a day, questioned the program’s cost-efficiency, as well as its potential for technical malfunctions and abuse. But BVR was funded by the UNDP and international donors, which had sunk $40 million into the Commission, and the new form of registration has not come up as an issue.

Another money problem stoked political ire against the NEC when it substantially raised the registration fees for opposition candidates. The smaller parties took Thorpe to task for “incompetence, poor planning, and deliberate attempts to frustrate the oppositions’ chances,” as the Sierra Leone Telegraph editorialized. When President Koroma offered to subsidize the other candidate registration fees, he raised more ethical questions. The international community condemned the move and fees were eventually lowered.

Former Colonizer Makes Good

The United Kingdom became conspicuously involved with its former West African colony when it sent several thousand troops to end Sierra Leone’s extended, sporadic civil war—made possible by Liberia’s Charles Taylor and Sierra Leone’s lucrative-metals mining, among other things—from 1991 to 2002. The war, which went through many phases with half a dozen factions, became known globally for creating “conflict diamonds” and for the hacking off of limbs by the rebel forces. Between 50 and 75 thousand people died with thousands more dismembered and millions displaced.

In 2000, with United Nations peacekeepers captured by rebel militias and Freetown in danger once again, Prime Minister Tony Blair ordered military operations to evacuate European and British citizens. The mission was quickly expanded by commanders on the ground who secured the capital and airport. Subsequently the British committed to stabilizing the country through counterinsurgency methods and rebuilding the Sierra Leone Army. Along with the paratroopers and special forces came dozens of development and reconstruction agencies to implement various aid packages. The Brits revived Sierra Leone and, along with the UN and thousands of troops, saw the nation through to the May 2002 presidential elections: President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah of the SLPP defeated Ernest Bai Koroma in a landslide.

Blair—blessed by counterinsurgency success and arguably responsible for a new peace and development regime—was considered a hero by many Sierra Leoneans and retained a connection to the land. During his last visit as prime minister in 2007 (a few months before the election), he began work on his African Governance Initiative to promote private investment. He returned to meet with President Koroma and encourage tourism in 2008 and again in 2009.

Blair has praised the good work of Koroma on several occasions, and wrote in 2010: “Since [his 2007 election victory] has taken on the challenges faced by his country, one by one.”

After Blair labeled Koroma a “visionary leader” of Africa, Sierra Leone People’s Party presidential candidate Julius Bio Maada called Blair out (as he’d done before) for picking sides. Maada wrote at the Huffington Post in January 2012

If our President is to be believed, then Sierra Leone is booming. Supported by Tony Blair and international lobbyists, he has taken this message around the world. But good PR is no substitute for the truth…..

For ordinary Sierra Leoneans, life has become much harder. Rice, flour and fish—the essential foodstuffs of our people—have doubled in cost since 2007. Fuel prices have rocketed. Five million Sierra Leoneans remain in desperate poverty. This decline is in contradiction to a government that portrays itself as spearheading an economic boom.

Conclusion

International intervention has reset Sierra Leone on a hopeful path. A string of transparent and peaceful elections are an appropriate and welcome metric of progress. Also, it is important that the reduction in outside government aid and development funds due to the global financial collapse be offset by private enterprise where beneficial. Yet in the drive to make Sierra Leone safe for forieign investment and capital development—in part by creating an international election apparatus—there is a danger of leaving the ordinary Sierra Leonean with no recourse against Freetown’s champions of Western growth.

By Michael Quiñones