There are echoes around the world about migration, what qualifies as a “deserving” applicant for asylum, and who has earned the right to move freely. Recently, an image was released of a father and daughter who drowned attempting to cross the border into the United States. The image was reminiscent of Alan Kurdi, a 3-year-old Syrian boy whose body washed ashore after attempting to make the journey to Europe in 2015. Despite Europe closing their borders, people are still coming. And I am here, years later, learning about it while my own country makes highly questionable choices about their immigration policy. These photos share in their tragedy, desperation, and a family’s journey for a better life, connected even though they are a continent away.

Detaining people, caging children, holding them in former military bases, and treating them like criminals, is wrong. Yet, the world continues to do it.

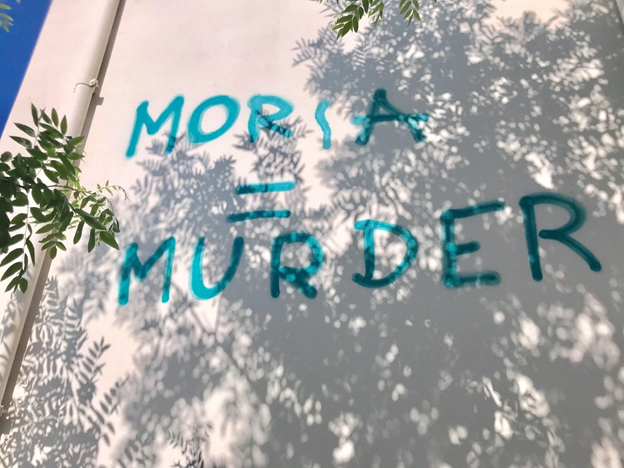

Last week our group visited a playground that was recently created for refugee children living in Moria and Olive Grove (the overflow of Moria camp). Walking between the gated official camp and the unofficial mix of tents and tarps strung together to make haphazard homes was an uncomfortable experience. Being aware of my privilege and status as a visitor, walking into a space where I do not belong, is not something I have noticed many people consider. Earlier that week I met an undergraduate journalism student from Princeton. Her group, in Lesvos for a few days, spent time touring the camps on the island, some intent on “exposing” specific issues. Touring someone’s suffering, the place that has taken every step to remove a person’s dignity, should not be a readily available day trip. Witnessing world issues and reporting on them are important, but keeping spaces accessible to all forms of visitors is an intrusive version of tourism disguised as guided lessons. The ability to consider these spaces as sensitive, and those who live in them as real people with skills and lives, who will experience the consequences of whatever you believe you are capable of “exposing”, should be a requirement before entering. How people occupy a space, and how they interact with inhabitants experiencing the trauma of a space of confinement, reveals a lot about a person’s character. Some believe they are entitled to a space based on their status, where they come from, or the name of their university.

“We are not a zoo.”

This is a phrase I’ve heard multiple times on Lesvos and similar areas that offer services to refugees, immigrants, and local populations. Organizations are tired of the countless visitors who stare at migrants like they are objects to be studied, rather than people to interact with and learn from. The island is a research hub. Overworked NGOs get a lot of attention and requests from visitors. Lesvos, and Mitilini in particular, pull scholars interested in migration, and volunteers looking to help, from all over the world. Due to Lesvos’ location as a European island in the Mediterranean, it is considered safe and desirable to Westerners compared to other refugee crises around the world. However, migrants are not on display for our benefit, whether that be for education, personal gain, or an “experience abroad”.

Walking in between Moria and Olive Grove was a minor glimpse into the realities of this migration “crisis”. Seeing the playground created by the organization Refugee for Refugees highlighted some great work by local NGOs. The large park was all built by hand. To bring color to the site, rocks were painted, and hand drawn animals decorated the fence to make children feel like they are safe and not enclosed in another jail. In the hours the playground is open, children, parents, and siblings are free to come and go as they please.

Freedom of movement is a human right. The ability to move, and to have the personal autonomy to make that decision, is natural. The persistent removal of these rights is stranding people in inhumane conditions that will have a lasting effect on their mental health.

The world’s slow response has consequences on thousands of innocent lives. If the system does not change, the world is condemning people to no life at all. The children in these camps will know nothing beyond the cages that confine them, the tents that cannot protect them from sweltering heat or below freezing temperatures, and the unsanitary conditions that leave them with spoiled food and unhygienic toilets.

Seeking a better life will of course come with great difficulty. No person making the journey across the borders of Europe or into the United States is ignorant to this fact. However, the journey should not be accompanied by torture, near death experiences, violence, and detainment in a camp that holds people in conditions not fit for animals.

Seeking freedom should not come with prison-like conditions that strip you of basic human rights. That is not the cost of a free life. This is a system that has failed, and that is not a radical statement. Anyone who has been near the camps on Lesvos, spoken to refugees waiting years for an appointment with an EASO (European Asylum Support Office) officer, or to one of the many NGOs trying to provide a service to make life a little more humane for those inside the camps knows this. Lawyers trying to assist refugees in their application process amid bureaucratic inadequacies and endless wait times know this. When a process is not working it must be changed.

Captivating and systematic read.