Following the announcement on March 4, 2013, that an 18-month old child in Mississippi had been cured of HIV with an early and rigorous regimen of anti-retroviral drugs, HIV/AIDS is briefly back in headlines in the U.S. Amid the flurry of excitement about this breakthrough in early-onset treatment, articles have abounded highlighting the important strides being made by the medical community, inspiring renewed hope that a cure for the virus is possible. While news about medical advancements is welcome, the overly technical language shaping this most recent conversation about HIV/AIDS is worrisome. The emphasis on a single cure, a magic bullet as it were, belies the social and economic causes and consequences of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the U.S.

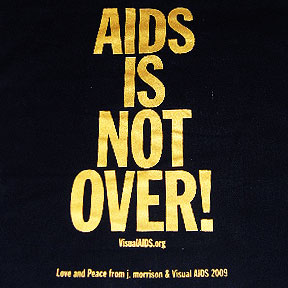

On March 9, 2013, the New School along with VisualAIDS and the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at CUNY Graduate Center, hosted a 3-day symposium to address the ongoing AIDS crisis. Under the slogan “Not Over,” students, educators, activists and filmmakers came together to discuss the continued impact of the disease on communities in the U.S. and around the world. One of the featured films during the symposium was The Other City, a documentary about the HIV/AIDS crisis in Washington, D.C. The film, directed by Susan Koch, explores the hidden side of the U.S. capital city, where the HIV/AIDS prevalence rate is estimated around 3%, making it the epicenter of the crisis in the United States. This fact gets lost among the glittering monuments and innumerable federal buildings.

Susan Koch’s film is well-made and worth watching. It provides a window into the lives of people written out of popular narratives of HIV/AIDS, namely intravenous drug users, sex workers and the homeless. However, one part of Koch’s film gave me pause. In the introductory credits to the film the audience is asked to guess which of the following cities has the highest rate of HIV/AIDS infection: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Dakar, Senegal, or Washington, D.C., USA. As the subsequent text revealed the answer to be Washington, D.C., I could not help but question the cynicism of such a ploy. The presumed U.S.-American audience is supposed to be shocked and dismayed that “our” country could be as bad as those “other” places.

Here, Haiti and Senegal—which can be read as a stand-in for the entire continent of Africa, stereotyped as AIDS-riddled despite wide-ranging differences in prevalence rates from country to country—become shorthand for a specific type of misery that is supposedly foreign. Images of the perceived despondency that besets the Global South have been used to justify all manners of interventionism, military and otherwise. In the arena of HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment, this has led to international conferences, round tables, NGO-led summits and all of the other accoutrements of liberal institutionalism’s psuedo-concern.

And what of Washington, D.C.? I find it odd that a city framed within a narrative of global suffering, lacks the same level of attention. Instead of traveling to “exotic locales” to build wells, why aren’t bright and enterprising college students scrambling for internships in Anacostia? Public Health programs in universities throughout the U.S. are churning out experts in all areas of “global health,” yet research for domestic health issues receives less and less funding.

Towards the end of The Other City, Washington Post reporter Jose Vargas says that the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Washington, D.C., embodies the racial and economic prejudices of the U.S. society as a whole. The epidemic also illustrates the continued hypocrisy in the U.S. regarding international scrutiny. While the U.S. government champions its efforts abroad and provides funding through initiatives like PEPFAR, it is unwilling to exercise the political will necessary to address an epidemic happening, literally, in its own backyard.