The following post is the third in our mini-series, taken from from graduate student Aaron Leaf’s microblog that documents his field research on Monrovia, Liberia’s post-conflict reconstruction efforts. Aaron was in Monrovia this January, and these posts reflect some of his spontaneous thinking about politics, culture, and the city.

Read Part I here and Part II here. Find out more about Aaron here.

My break in posts was due to a bout of Malaria I suffered last weekend. It happened about as quickly as one can get it after entering an endemic zone. I was laying in bed nauseous and sweating for a couple days. Weak as hell for a couple days after. I did manage to finish the Project Guttenberg version of Madam Bovary though and about half of James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State.

Oddly, it was Madame Bovary with all its descriptions of 19th century French medicine that had me thinking most about Monrovia. After the chemist warns young Leon that going to law school in Paris was the best way to contract Typhoid fever, I dragged myself over to the Chinese clinic for a Typhoid test. Thankfully negative.

The chemist Homais is by far the most interesting character and represents an arrogant modern man who has replaced faith in God with faith in what we know now as terribly outmoded science. He sees himself as superior to the doctors and even the state which threatens to shut him down for practicing medicine without a license. Fair enough, the doctors are largely superstition peddlers bleeding people to death. But it’s the chemist with his belief in cutting edge science who pushes the doctor, Charles Bovary, into an experimental surgery that ends up destroying his reputation.

Flaubert’s satirical take on “modernity” works rather well when read together with Scott’s chapter on high-modernist city planning. The architect and planner Le Corbusier is a kind of Homais character who completely rejects the norms of the past, trying to reorganize the city according to “SCIENCE.”

I’m not going to put too much emphasis on this, I’m just free associating here, except to say that this kind of hubris is apparent in both foreign aid projects as well as a local desire, here in Liberia, for governance by technocratic elite. I think this was part of the great appeal of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s government, a coalition of international and local technocrats would, using “SCIENCE,” engineer macroeconomic stability, attract foreign investment, build peace and voila, middle income status by 2020.

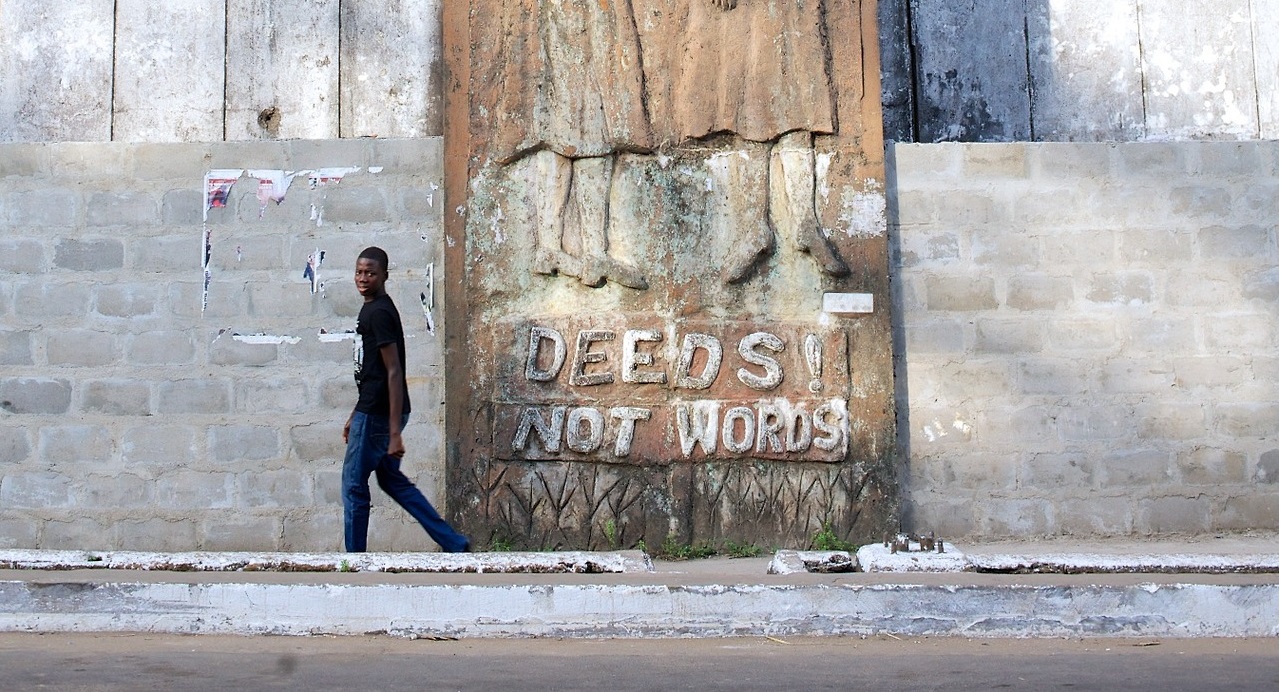

This hasn’t happened, obviously, and people are getting restless, especially with the weekly high-level corruption scandals, the climbing exchange rates and the continuing demolition of people’s homes and businesses in the name of creating a Monrovia more suitable for investment.

I know many see development as a complex engineering problem like building a bridge or launching a rocket but on this end it feels much more like experimental 19th century surgery, before anesthetic.